The decision over the weekend to ban the purchase of newly mined and refined gold from Russia is the latest effort by the United States, Britain and their allies to notch up the wave of sanctions concentrated on Russia in response to its four-month-old invasion of Ukraine.

The announcement, made as President Joe Biden and other leaders from the Group of 7 nations gathered for meetings this week in Germany, builds on steps already taken to cut off Russia from the international financial system, deprive it of additional revenues that are helping fund its war in Ukraine and punish President Vladimir Putin of Russia and wealthy business executives in his circle.

Ukraine’s allies have already prohibited most trade with Russia, frozen hundreds of billions of dollars of assets belonging to the Bank of Russia held in their own financial institutions and blocked Russian banks from using the messaging system, known as SWIFT, that undergirds the system of international payments.

Russia, one of the world’s biggest producers of gold, cranked up the mining of new gold to compensate for some of the paralyzed assets, said Christopher Swift, a national security lawyer at Foley & Lardner.

The Bullion Market Association in London, a major hub of the global gold trade, had already suspended transactions with six Russian silver and gold refineries in March.

Swift, who previously worked at the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, said: “In order to make up for reserves held by Russian companies and oligarchs, they brought new gold online. The G-7 is shutting down access to this new gold.”

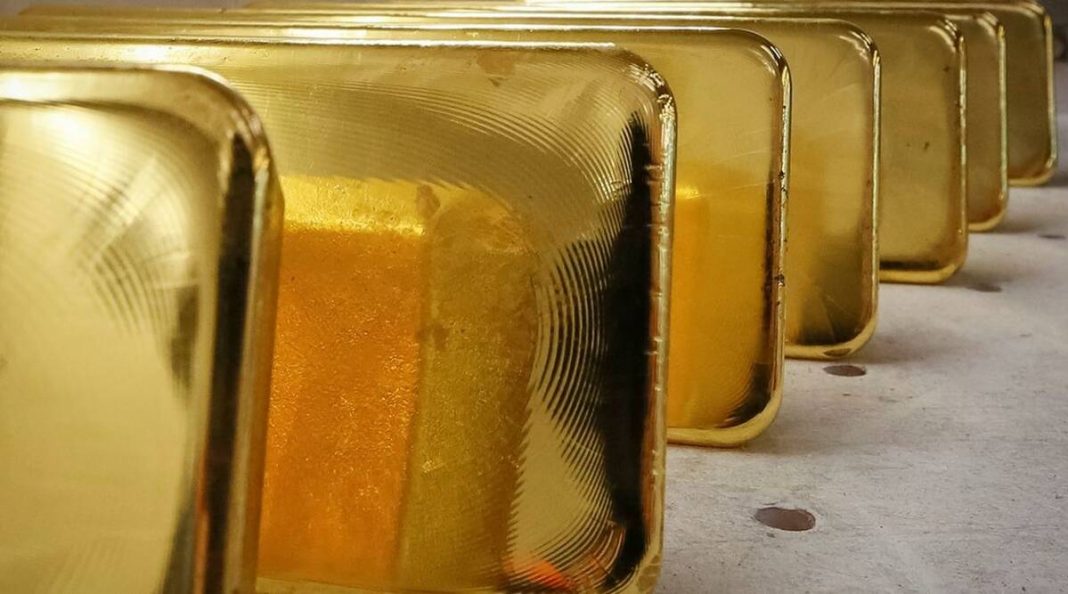

Russia’s billionaire business magnates have been buying gold bullion in an attempt to blunt the impact of the sanctions. Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain underscored the point Sunday, saying the move would “directly hit Russian oligarchs.”

Whether this latest move, which is scheduled to be formally announced Tuesday, will also — in Johnson’s words — “strike at the heart of Putin’s war machine” is more debatable.

Ukraine’s allies have struggled to keep the pressure on and deprive Putin of resources for his war machine without putting their own economies at too much risk. The balancing act is particularly difficult for the European Union, which heavily depends on Russian oil and gas.

The G7 countries’ ban on gold imports from #Russia will deprive it of about $ 19 billion a year — #US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken. pic.twitter.com/26EyXOF59w

— NEXTA (@nexta_tv) June 26, 2022

Skyrocketing oil prices combined with an enormous appetite for fuel around the world means Russia has been raking in even more money from the sale of crude than it did before the war, despite selling at a discount.

After weeks of tense negotiations, the EU agreed last month to largely ban the import of Russian oil by the end of this year as well as prohibit European countries from insuring tankers carrying Russian oil. But so far the question of whether to ban Russian gas — for which it is much harder to find a substitute than oil — has been off the table. Germany’s government and industrial leaders have warned that a gas embargo would be catastrophic for its economy.

Talking about the sanctions rollout, Jeffrey Schott, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, said the buildup of pressure on the Russian economy “is going as planned.” He added that “if there’s any surprises, it’s how coherent the policy coordination has been across the Atlantic and East Asian countries.”

The various alliance members have been casting about for ways increase the penalties one notch at a time. The gold ban “gives the governments of the G-7 some runway and the opportunity to ramp up,” said Andrew Shoyer, a lawyer at Sidley who advises companies on compliance with sanctions.

Good @opinion piece from @davidfickling on why a ban on Russian gold isn’t about to upend the market. Spoiler: Russia doesn’t export all that much.https://t.co/kGwxu6WHK8 pic.twitter.com/qVMKaC8hJc

— ClaraFerreiraMarques (@ClaraDFMarques) June 28, 2022

The distinction between newly mined and refined gold, and gold that was exported or purchased before the ban, is in line with the sanctions framework that prohibits new investment in Russian companies, while permitting existing investments, Shoyer said.

The new ban is also aimed at depriving Russia of additional revenues earned from exporting gold, which is used for jewelry, in some industrial processes and for investment. As is often the case during crises, the purchase of gold for investment jumped after the coronavirus pandemic started upending the global economy. Investors expect it to retain its value. Central banks, including the Federal Reserve, had bought Russian gold through intermediaries.

Last year, Russia earned more than $15 billion from its gold exports, according to the British government. Since gold is widely held in reserve by central banks around the world, Russia had a ready market.

“Russia is a big producer of gold, and it is a reserve asset,” said Lucrezia Reichlin, a professor at the London Business School. “If they cannot sell, then that source of income is gone.”

After the early rounds of sanctions had stopped much of its existing international gold trade, Russia’s central bank announced that it would resume buying domestically produced gold, which was also seen as a way of helping to prop up its currency. The gold held by Russia’s central bank is estimated to be worth $100 billion to $140 billion.

“Fundamentally this is an incremental tightening of the sanctions rather than a significant escalation,” Swift said. “If your goal is to undermine Russia’s economic ability to wage war in Ukraine, this is a necessary but not sufficient measure.”

But he added, “If the G-7 wants to have a strategic effect then they really need to think about what they’re going to do about Russian gas.”