In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution—driven by new general-purpose technologies like the steam engine and mechanized production—spurred a dramatic split in global fortunes known as the “Great Divergence.” By 1800, most countries were poor: Life expectancy was below 40, and literacy rates rarely exceeded 12%, with “almost no income gap” between regions. By 1900, however, industrialized powers enjoyed vastly higher incomes and lifespans than those left behind.

Artificial intelligence (AI) may play a similar role today. AI is emerging as a new general-purpose technology with enormous transformative potential. It can expand opportunities and unlock breakthroughs in education, healthcare, and productivity. Yet, as we analyze in UNDP Asia-Pacific’s new report “The Next Great Divergence,” AI also carries a serious risk of widening inequality between countries.

This may sound counterintuitive. Many believe AI will level the playing field and unlock new leapfrogging opportunities in education, health care, and productivity. And it can. But our analysis shows that without deliberate intervention, the centrifugal forces may dominate, widening gaps between nations and setting the stage for a “Next Great Divergence.”

Socrates and Edison were both wrong

Every major technological revolution arrives with a mix of hysteria and hype. In ancient Athens, Socrates worried that writing would weaken memory, an irony preserved for us only because Plato wrote his claims down. Two millennia later, Thomas Edison predicted that motion pictures would replace textbooks, believing film would teach “every branch of human knowledge.”

Both misjudged the role of technology. They focused on whether new tools would replace existing ones, rather than how capabilities would spread. Today, we replay that same binary debate. Will AI replace work, or solve every human problem? In arguing about what AI is, we ignore where it is landing and who stands to benefit.

The real issue is not the nature of the technology, but the geography of its impact. We are focused on what AI can do and not enough on where it is doing it.

AI lands in a deeply unequal world

AI is not entering a level playing field. It is arriving in a world marked by extraordinary inequality. Nowhere is this more evident than in Asia and the Pacific, the most economically diverse region globally. Incomes differ by nearly two hundred times between the richest country, Singapore, and one of the poorest, Afghanistan.

These divides shape two structural asymmetries: a capability gap and a vulnerability gap, which together amplify unequal impacts of AI across countries.

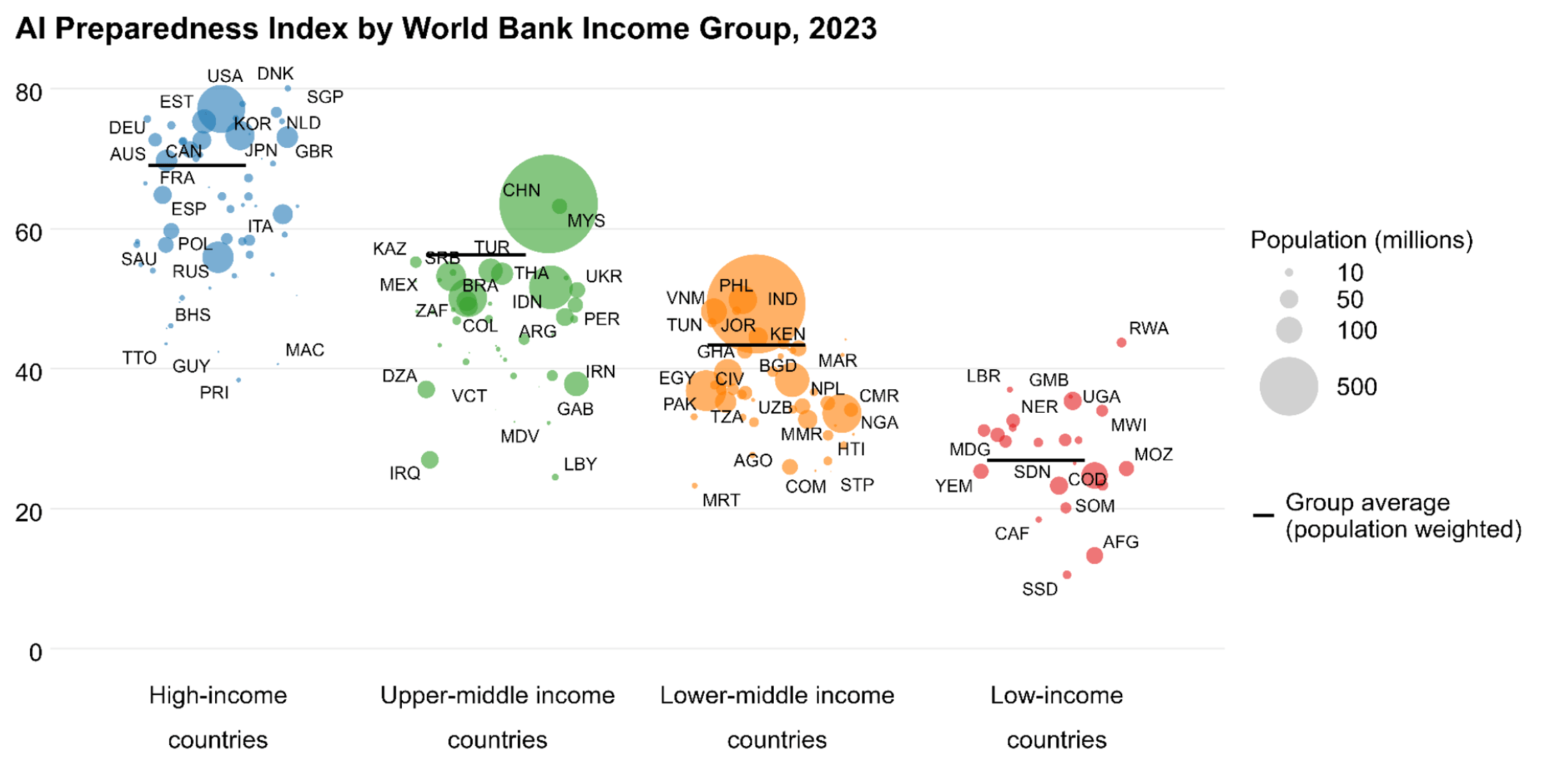

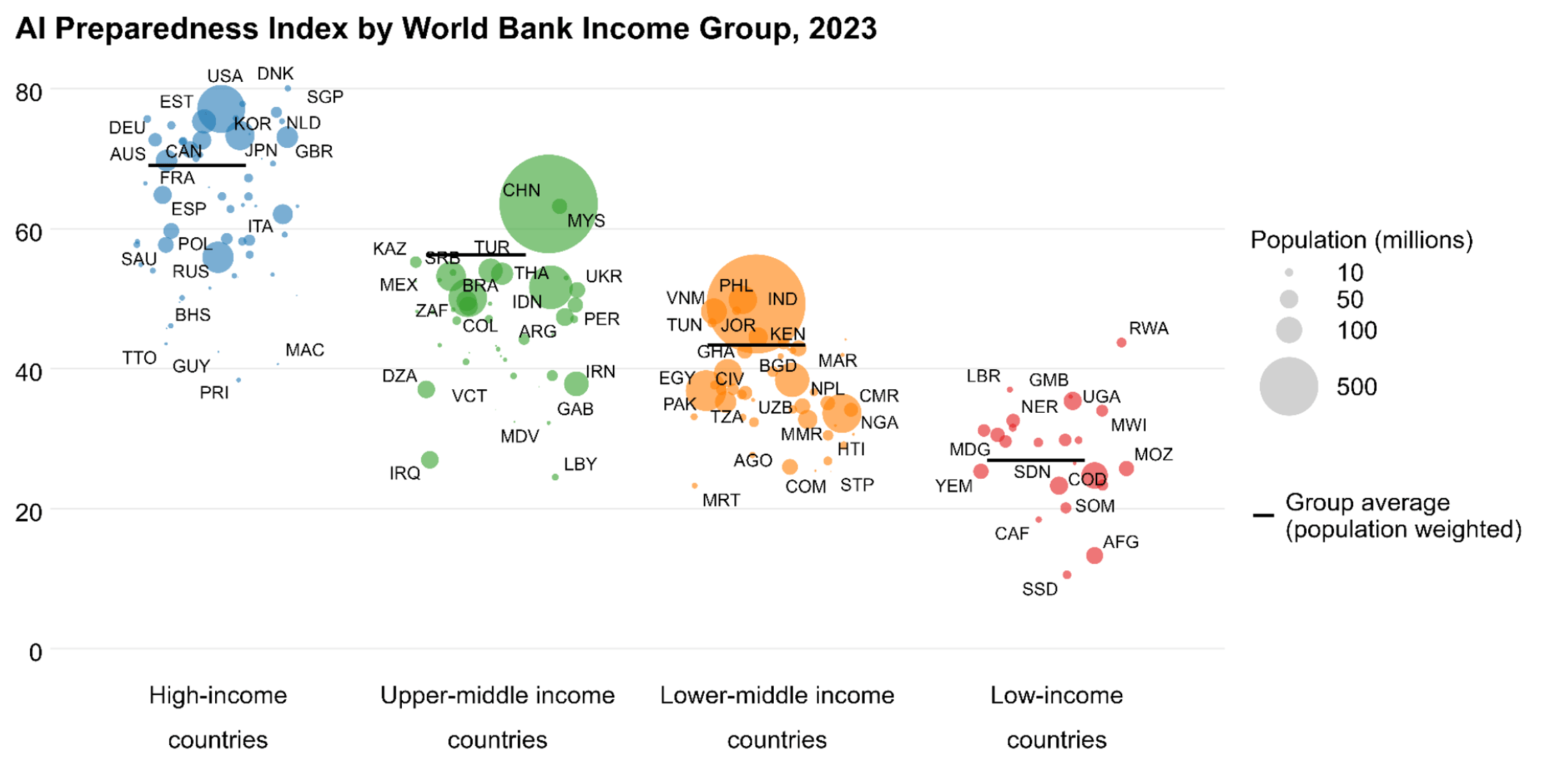

Figure 1. The world is unequally prepared for AI, which will manifest itself in the uneven accrual of dividends and disruptions

Source: UNDP; IMF AI Preparedness Index (2023).

The capability gap

Innovation is concentrating quickly at the top. The IMF’s AI Preparedness Index shows that high-income countries are already far better positioned to benefit from AI. Many low-income countries still struggle with basic electricity, broadband, and foundational digital infrastructure.

The internal contrasts within Asia-Pacific are equally striking. Six economies alone account for more than 3,000 newly funded AI firms. China accounts for nearly 70% of global AI patents. Several economies in the region are now major AI developers.

Yet basic digital access remains a major barrier across much of the region. Roughly one quarter of Asia-Pacific’s population remains offline. Even where networks exist, a vast skills deficit persists. Only about one in four urban residents and fewer than one in five rural residents can perform a basic spreadsheet calculation. The capacity gap is also gendered: In South Asia, women are up to 40% less likely than men to own a smartphone.

These gaps mean that while some countries are rapidly building domestic AI ecosystems, many are not yet able to participate in the AI economy at all.

The vulnerability gap

While capability concentrates at the top, risks radiate downward.

Labor markets illustrate this clearly. Women’s jobs are nearly twice as likely as men’s jobs to face high exposure to AI-driven automation. About 4.7% of female employment in a recent sample fell into high-exposure categories, compared with 2.4% for men.

Generational divides are also emerging. Employment for workers aged 22-25 in high-exposure occupations has fallen by about 5% in recent years, suggesting that AI is reducing entry-level opportunities even as older workers experience productivity gains.

Beyond jobs, AI’s energy needs introduce new environmental vulnerabilities. Electricity consumption by data centers may nearly triple by 2030. Countries with fragile, fossil-fuel-based power systems risk hosting energy-hungry “data farms” for global AI, bearing environmental costs while capturing little of the economic value.

Taken together, the capability and vulnerability gaps are producing a world in which AI benefits concentrate in the better-positioned countries, while disruptions fall most heavily on populations least prepared to manage them.

Three strategic choices

A widening divide is not inevitable. Policymakers have a window to steer AI toward convergence through three strategic choices.

1. Don’t repeat the “One Laptop per Child” mistake

The One Laptop per Child initiative showed that technology will fail if deployed into environments without the “soft infrastructure” needed to use it. Laptops were delivered, but without trained teachers, high-quality localized content, and reliable connectivity, the devices were often unused or misused.

The same risk exists with AI. Pilots can appear promising, but if people lack the skills to use, trust, or meaningfully benefit from AI tools, adoption will stall.

With fewer than 20% of rural residents in the Asia-Pacific capable of basic digital tasks, human capital must be the priority. This means investing in computer science and data science education, training civil servants in data governance, and embedding AI literacy across society. Empowering people must come alongside deploying systems.

2. Build regional AI public goods

Few countries can build a full AI ecosystem on their own. To reduce dependency on a handful of technology giants, countries should treat core AI enablers—compute infrastructure, data, and foundational models—as regional public goods.

Regional compute and data commons would allow countries to pool resources and gain access to shared capabilities. For example, an ASEAN-wide cloud for AI research or a South Asia initiative to create local-language large language models could widen access and strengthen collective bargaining power.

A regional approach also enables a “green AI industrial policy”. As data center demand grows, governments can require energy-efficient architectures and renewable-powered compute expansion, ensuring sustainable growth rather than replicating past patterns of extractive digital infrastructure.

3. Tailor AI roadmaps to local capacity

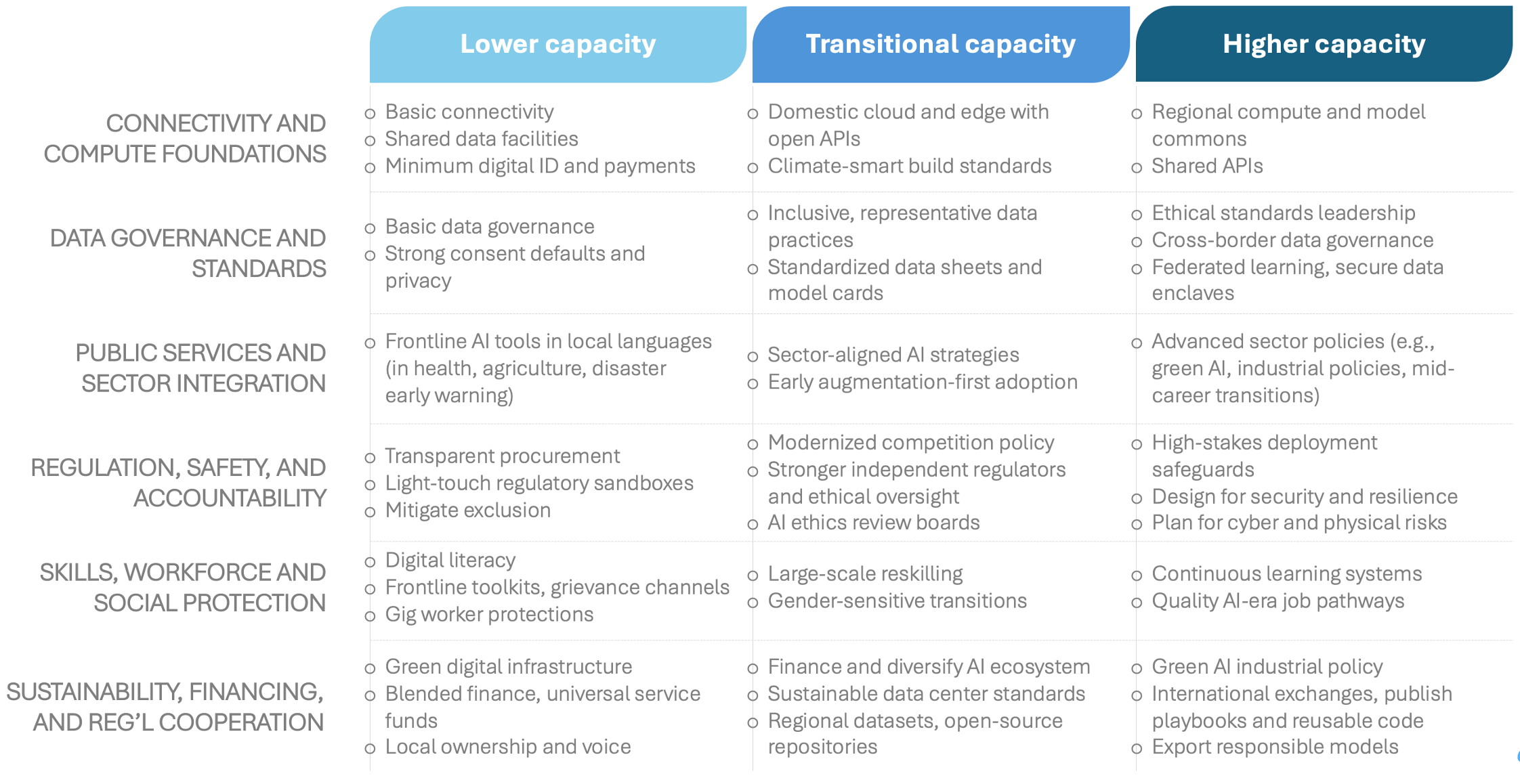

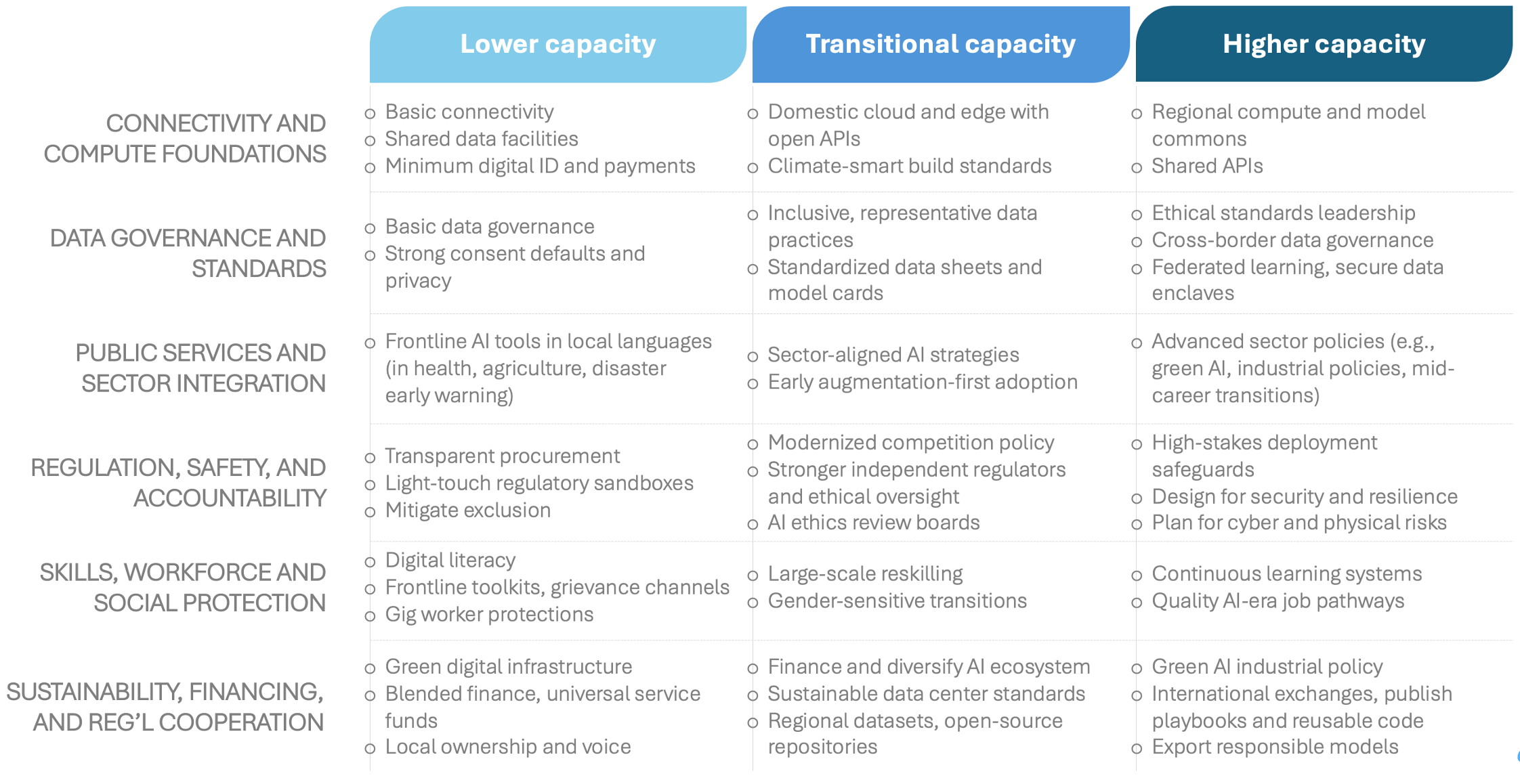

A single AI strategy cannot fit all countries. Approaches must reflect starting points (Table 1):

- Lower-capacity contexts will need to focus on basic connectivity. Offline-capable AI for healthcare triage or agricultural support through feature phones can deliver real value where broadband is limited.

- Transitional-capacity economies can scale proven pilots, build civic data infrastructures, and establish privacy and governance frameworks that avoid dependency and scattered experiments.

- Higher-capacity countries have the opportunity to lead on standards, safety, and sustainability. They can strengthen regulatory oversight, push for energy-efficient AI research, and contribute regionally by sharing models and expertise.

Tiered strategies help ensure that countries build from foundations they can sustain, rather than adopting technologies mismatched to their institutional realities.

Table 1. Roadmaps tailored to different starting points

Source: The Next Great Divergence, UNDP, 2025.

Leave no mind behind

AI is becoming the general-purpose infrastructure of the 21st century, as fundamental as electricity or roads. It is critical that we don’t allow access to this infrastructure to be deeply unequal. By investing in human capital and institutions, treating connectivity and computing power as public goods, and designing inclusive, tiered roadmaps, we can ensure that AI’s immense productivity potential is shared.

If the 21st Century marks the start of the next Great Divergence, it will not be because of AI alone. It will be because we did not act.

Counsellor Perfect is a counselling psychologist and ADR practitioner

Counsellor Perfect is a counselling psychologist and ADR practitioner