The Democratic Republic of Congo is in turmoil – fighters from the notorious M23 rebel group have been surging through the country’s east, battling the national army and capturing key places as they go.

In just a fortnight, thousands of people are said to have been killed and the fighting has sparked an ominous war of words between DR Congo and its neighbour, Rwanda.

So how did DR Congo – the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa – get here?

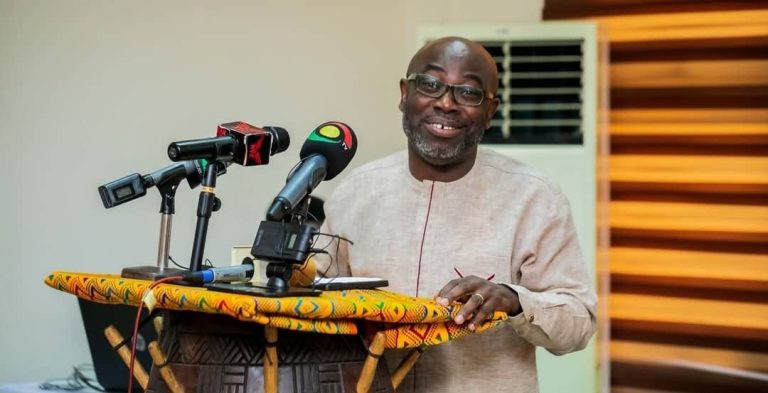

The origins of this complex conflict can be understood through the story of one man – M23 leader Sultani Makenga, who is the subject of various war crime allegations.

He is sanctioned by the US of using child soldiers, which he has denied. The UN has accused him of being responsible for sexual violence.

To go back through Makenga’s life so far is to look into decades of warfare, intermittent foreign intervention and the persistent lure of DR Congo’s rich mineral resources.

His life began on Christmas Day in 1973, when he was born in the lush Congolese town of Masisi.

Raised by parents of the Tutsi ethnic group, Makenga quit school at the age of 17 to join a Tutsi rebel outfit across the border in Rwanda.

This group, named the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), were demanding greater Tutsi representation in Rwanda’s government, which at the time was dominated by politicians from the Hutu majority.

They also wanted the hundreds and thousands of Tutsi refugees who had been forced from the country by ethnic violence to be able to return home.

For four years, Makenga and the RPF fought the Hutu-dominated army in Rwanda. Their battle was enmeshed with the 1994 genocide, when Hutu extremists killed 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

When looking back at this time in a rare 2013 interview, Makenga stated: “My life is war, my education is war, and my language is war… but I do respect peace.”

The RPF gradually seized more and more land before marching into Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, and overthrowing the extremist Hutu government – many of whom fled into what is now DR Congo.

With the RPF in power, Makenga was absorbed into the official Rwandan army and rose to the rank of sergeant and deputy platoon commander.

“He was very good at setting up ambushes,” one of Makenga’s fellow RPF fighters told the Rift Valley Institute non-profit research organisation.

His progress in the Rwandan army hit a ceiling however. The fact that he only had a basic education and spoke broken French and English was “an obstacle to his military career”, the Rift Valley Institute said.

Makenga is also said – to this day – to be very reserved and to struggle with public speaking.

In 1997, he was part of the Rwanda-backed forces who ended up seizing power in DR Congo, ousting long-serving ruler Mobutu Sese Seko. In his place they installed veteran Congolese rebel leader Laurent Kabila.

However, Makenga began to clash with his superiors – he was arrested by the Rwandan authorities after refusing orders to return to Rwanda, a UN Security Council report said.

He was therefore imprisoned for several years on the island of Iwawa.

Meanwhile, relations between Kabila and Rwanda’s new leaders deteriorated.

Rwanda had sought to crush the Hutu militiamen who were responsible for the genocide but had fled across the border in 1994. Rwanda’s fear was that they could return and upset the country’s hard-won stability.

But Kabila had failed to stop the militants from organising and he also started to force out Rwandan troops.

As a result, Rwanda invaded DR Congo in 1998. When Makenga was released from prison, he was appointed to serve as a commander on the front line with a Rwanda-backed rebel group.

Over the years, he gained a reputation for being highly strategic and skilled at commanding large groups of soldiers into battle.

After Rwandan troops crossed into DR Congo, there was a surge in discrimination against the Tutsi community. Kabila alleged that Tutsis supported the invasion, while other officials incited the public to attack members of the ethnic group.

Makenga – still in DR Congo – accused the Congolese leader of betraying Tutsi fighters, saying: “Kabila was a politician, while I am not. I am a soldier, and the language that I know is that of the gun.”

Several neighbouring countries had been drawn into the conflict and a large UN military force was deployed to try to maintain order.

More than five million people are believed to have died in the war and its aftermath – mostly from starvation or disease.

The fighting officially ended in 2003 but Makenga continued to serve in armed groups opposed to the Congolese government.

In the spirit of reconciliation, Tutsi rebels like Makenga were eventually amalgamated into the Congolese government’s armed forces, in a process called “mixage”.

But the political sands in DR Congo are ever shifting – Makenga eventually defected from the army to join the rising M23 rebellion.

The M23 had become increasingly active in DR Congo’s east, stating that they were fighting to protect Tutsi rights, and that the government had failed to honour a peace deal signed in 2009.

Makenga was elevated to the rank of an M23 general, then soon after, the top position.

In November 2012 he led the rebels in a brutal uprising, in which they captured the city of Goma, a major eastern city with a population of more than a million.

DR Congo and the UN accused Rwanda’s Tutsi-dominated government of backing the M23 – an allegation which Kigali has persistently denied. But recently, the official response has shifted, with government spokespeople stating that fighting near its border is a security threat.

By 2012, Makenga and others in the M23 were facing serious war crimes allegations. The US imposed sanctions on him, saying he was responsible for “the recruitment of child soldiers, and campaigns of violence against civilians”. Makenga said allegations that the M23 used child soldiers were “baseless”.

Elsewhere, the UN said he had committed, and was responsible for, acts such as killing and maiming, sexual violence and abduction.

Along with asset freezes, Makenga was facing a bitter split within the M23. One side backed him as leader while the other backed his rival, Gen Bosco Ntaganda.

The Enough Project, a non-profit group working in DR Congo, said the two factions descended into a “full-fledged war” in 2013 and as a result, three soldiers and eight civilians died.

Makenga’s side triumphed and Gen Ntaganda fled to Rwanda, where he surrendered to the US embassy.

Nicknamed the “Terminator” for his ruthlessness, Gen Ntaganda was eventually sentenced by the International Criminal Court (ICC) to 30 years for war crimes.

However, months after Makenga’s triumph, another, larger threat appeared. The UN had deployed a 3,000-strong force with a mandate to support the Congolese military in reclaiming Goma, prompting the M23 to withdraw.

The rebel group was expelled from the country and Makenga fled to Uganda, a country which has also been accused of supporting the M23 – an allegation it denies.

Uganda received an extradition request for Makenga from DR Congo, but did not act on it.

Eight years passed. Dozens of other armed groups roamed the mineral-rich east, wreaking havoc, but the Congolese authorities were free of the most notorious militants.

That is, until 2021.

Makenga and his rebels took up arms again, capturing territory in North Kivu province.

Several ceasefires between the M23 and the Congolese authorities have failed, and last year a judge sentencing Makenga to death in absentia.

During the M23’s latest advance, in which the rebels are said to be supported by thousands of Rwandan troops, Makenga has barely been seen in public.

He instead leaves the public speeches and statements to his spokesperson, and Corneille Nangaa, who heads an alliance of rebel groups including the M23.

But Makenga remains a key player, appearing to focus on strategy behind the scenes.

He has said his relentless fighting has been for his three children, “so that one day they will have a better future in this country”.

“I shouldn’t be seen as a man who doesn’t want peace. I have a heart, a family, and people I care about,” he said.

But millions of ordinary people are paying the price of this conflict and if he is captured by the Congolese forces, Makenga faces the death penalty.

Yes he is undeterred.

“I am willing to sacrifice everything, ” he said.