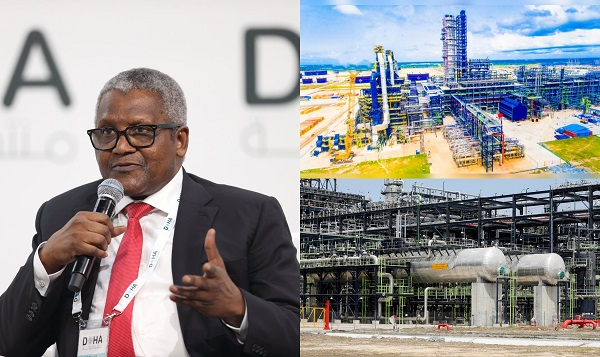

Facing escalating conflicts across numerous areas, the Dangote Refinery is fighting for survival while competitors stand firm. Each day brings renewed resistance, ranging from blocked access to crude oil and persistent fuel imports to confrontations with labour unions. Yet recent events have arguably solidified the founder’s reputation as a tenacious combatant. This report by DARE OLAWIN examines the refinery’s ongoing quest for calm and solid footing following many months of severe challenge.

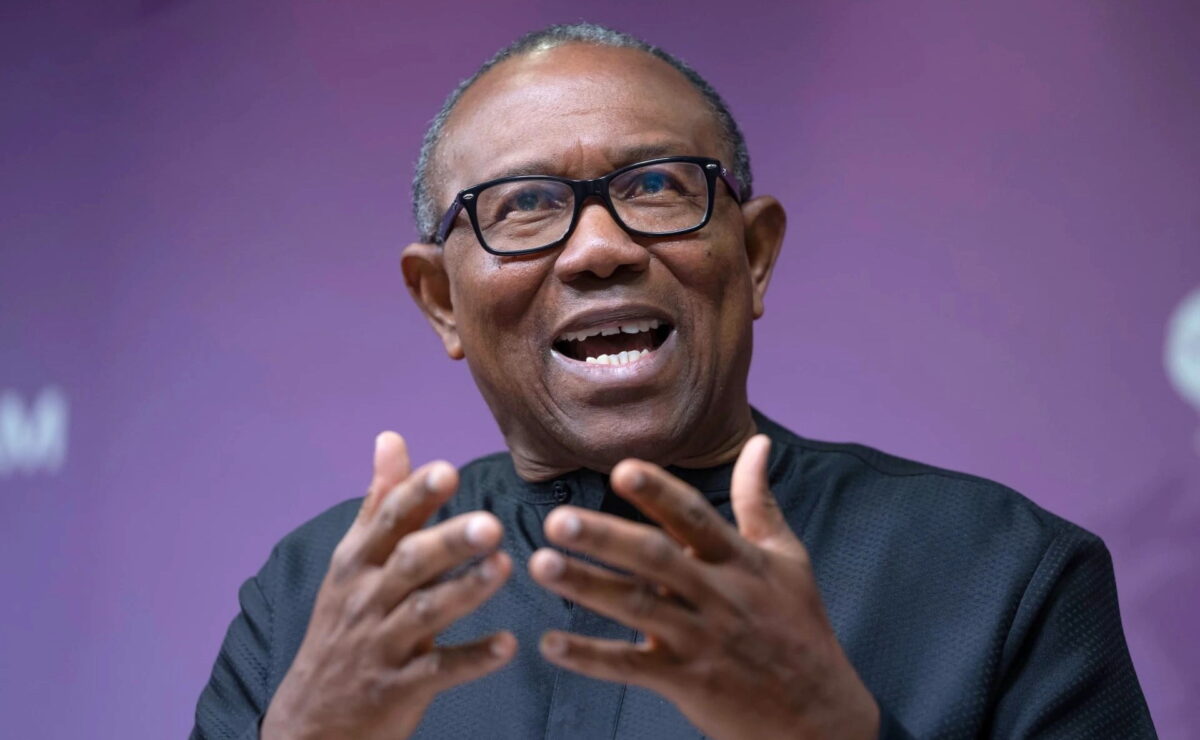

If he had had a premonition of the battles that awaited him in the refining sector, Alhaji Aliko Dangote himself testified that he would not have built the Lekki $20bn plant. But despite this regret, the billionaire businessman remains resolute; he said he had been fighting battles all his life, though he confessed that the mafias in oil are stronger than the mafia in drugs.

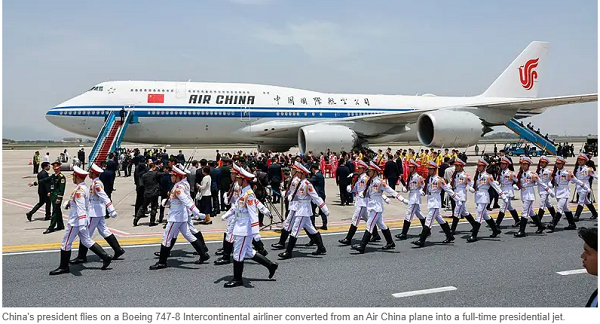

When the $20bn oil refinery came on stream in 2024, Nigerians heaved a sigh of relief. For decades, the nation had endured long queues and the shame of importing petroleum products despite being Africa’s largest crude producer. This was because the government-owned refineries remained dormant despite billions of dollars spent on turnaround maintenance. The Dangote refinery was hailed as the game-changer, a 650,000-barrel-per-day behemoth that would finally break the chains of fuel dependency.

But two years on, the refinery found itself locked in battles that threaten its promise. Instead of a smooth take-off, it grappled with opposition on all fronts, from alleged crude supply denials and international oil traders to entrenched unions and import cartels.

At one time, it was the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited; at another time, it was the regulator. Later, the marketers, depot owners and importers joined the battle. When it seemed the refinery had begun to know peace and stability, the workers’ union mobilised tanker drivers to picket it over allegations of disallowing unionisation among its workers.

Aliko once said he planned to build a refinery after the government of the late Umaru Yar’Adua stopped the acquisition of the Port Harcourt and Warri refineries by a consortium of which he was a part. Since inception, the facility, which was initially designed to be sited in the Olokola Free Trade Zone in Ogun State, faced a three-year delay due to the inability of the Dangote Group and the Ogun State Government to agree on issues.

Last year, Dangote disclosed that the delay in securing a site for his petrochemical facility in Ogun State resulted in a $500m loss for his conglomerate. He attributed the financial setback to the protracted process of acquiring Olokola land for a petrochemical facility, which cost him $500m out of the $2.5bn initial drawdown on bank loans.

After the three years wasted in Ogun, the company secured land in the Lekki Free Zone, Lagos, and the journey started. The billionaire recalled how he encountered difficulties in getting capable and trusted engineering, procurement and construction contractors to handle the project, noting that one of the global contractors once tried to sabotage the project.

After about 10 years, the deed was done. The plant was ready. Nigerians were eager to have access to affordable fuel. It was a historic moment for a nation whose refining capacity was almost zero for decades. Unaware of what was on the minds of the existing traders in the downstream, Dangote went to the CEO Forum in Rwanda to say Nigeria would no longer import any fuel.

“Nigeria shouldn’t import anything like gasoline; not one drop of a litre. We have enough gasoline to give to at least the entirety of West Africa and diesel to give to West Africa and Central Africa. We have enough aviation fuel to give to the entire continent and also export some to Brazil and Mexico,” he said.

When Dangote made this comment, the NNPC was the sole importer of petrol due to subsidy payments. The comment triggered a subtle competition in the sector. Dangote refinery was supposed to start petrol production in June 2024, but the crude producers reportedly exported their product, forcing the 650,000-barrel-per-day facility to import feedstock.

Crude war

In June 2024, the Vice President of Oil and Gas at Dangote Industries Limited, Devakumar Edwin, accused international oil companies of plans to frustrate the survival of the refinery. Edwin said the IOCs were “deliberately and wilfully frustrating” the refinery’s efforts to buy local crude by hiking the cost above the market price, thereby forcing the refinery to import crude from countries as far away as the United States.

He added that though the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission was trying its best to allocate crude oil for the refinery, “the IOCs are deliberately and wilfully frustrating our efforts, making the refinery pay a $6 premium above the market price.”

Edwin said, “It appears that the objective of the IOCs is to ensure that Nigeria remains a country which exports crude oil and imports refined petroleum products.”

The refinery also traded words with the NUPRC, accusing the upstream regulator of failing to enforce the domestic crude supply obligation. The NUPRC defended itself, arguing that it had facilitated the domestic supply of crude oil to the Dangote refinery and other refineries using the monthly production curtailment platform.

However, oil producers, under the aegis of the Independent Petroleum Producers Group, warned against being forced to sell crude oil to the Dangote refinery. The IPPG said some of its members already owned and were supplying crude oil to local refineries but insisted that the NNPC was in a good position to mitigate the crude supply shortfall faced by local refiners by leveraging its statutory crude allocation for meeting local domestic consumption.

The IPPG said some of its members received letters from the Dangote refinery for crude supply nominations and faulted the approach as bringing them under an obligation, saying it conflicted with the spirit of the willing-buyer, willing-seller framework prescribed by the Petroleum Industry Act 2021.

Naira-for-crude deal

As the battle for local crude supply escalated, President Bola Tinubu waded in, ordering the NNPC to sell crude to the Dangote refinery in naira. The idea was to strengthen the naira by reducing spending of foreign exchange earnings on the importation of crude and fuel into Nigeria.

The President’s Special Adviser on Revenue, Mr Zacch Adedeji, who also serves as Chairman of the Federal Inland Revenue Service, said the move would mitigate Nigeria’s heavy reliance on foreign exchange for crude oil imports, accounting for roughly 30 to 40 per cent of its forex expenditure.

The revenue chief said that by denominating crude oil transactions in naira, the government expects to significantly lighten its forex burden, with estimated annual savings of $7.3bn. It is also expected to reduce monthly forex expenditure on petroleum products to $50m from approximately $660m.

“Monthly, we spend roughly $660m on these exercises, and if you analyse that, that will give us $7.92bn in savings annually,” he stated.

War over direct fuel distribution

During President Tinubu’s visit to the refinery in June, Dangote revealed plans to do something that would shake the country. He later announced the deployment of 4,000 CNG-powered trucks to distribute fuel directly to filling stations and bulk buyers. This marked the beginning of another serious battle against the refinery.

Truck drivers, middlemen, DAPPMAN and others affected by the decision reacted angrily. The sector was truly shaken. Members of the Nigerian Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers shut down refineries and depots nationwide over allegations that drivers were not allowed to join the union.

The National Association of Road Transport Owners said they had lost all their customers to the Dangote refinery. They cried out over job losses. DAPPMAN said the refinery’s price reductions were designed to stifle importers whose cargoes were already at sea.

Depot owners alleged that Dangote sold petrol to international traders at ₦65 cheaper than it sold to local off-takers, claiming the company refused to sell to its members.

But Aliko Dangote said he had to protect his investment because marketers were not buying from him. According to him, DAPPMAN members demanded an annual subsidy of ₦1.5tn to enable them to match the refinery’s gantry prices.

The refinery alleged that its refusal to comply with the subsidy demand was the real reason behind the public criticisms and attacks in October. It reiterated that it had sufficient capacity to meet domestic demand and support exports, with about 500 million litres of fuel monthly.

Between June and September, it said the refinery exported 3,229,881 metric tonnes of petrol, diesel and aviation fuel, while marketers imported 3,687,828 metric tonnes within the same period.

From DAPPMAN, the refinery entered another battle with the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria, which picketed oil and gas facilities over allegations that Dangote sacked about 800 workers who joined the union. Dangote said those dismissed were sabotaging the refinery.

Expansion amid crisis

Amid the crisis, Aliko Dangote said he had begun expanding the refinery from 650,000 to 1.4 million barrels per day. This came as a surprise to many. The courage to expand despite crude shortages and stiff opposition was seen as highly ambitious.

But Dangote appears to have deep confidence in President Bola Tinubu. It appeared the duo held a closed-door meeting where undisclosed agreements were reached.

15% fuel import duty drama

A few days after Dangote announced the expansion plan, the Federal Government imposed a 15 per cent duty on imported petrol and diesel. The policy was meant to discourage fuel imports and support local refining. While refiners welcomed the move, importers warned it could raise fuel prices.

However, less than two weeks later, the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority announced that “the implementation of the 15 per cent ad valorem import duty on imported premium motor spirit and diesel is no longer in view.”

Though the government said the duty would be reintroduced in the first quarter of 2026, refiners expressed disappointment.

Otedola backs Dangote

Dangote’s billionaire friend, Femi Otedola, emerged as one of his strongest supporters during the crisis. He backed Dangote against accusations of monopolistic tendencies and criticised those resisting reform.

“But times have changed… With the Dangote refinery now supplying fuel locally, the old business model is crumbling,” Otedola said.

Officials of DAPPMAN told our correspondent that “Otedola is entitled to his opinion.”

Dangote winning?

With the resignation of regulators, some argued that Dangote had won the battle, but the war may be far from over. Dangote himself believes the vested interests he is confronting are powerful, but he insists he will never give up.

Conclusion

After months of bruising battles over crude supply, pricing, regulation, distribution, union politics and market share, the Dangote refinery appears to have carved out space for itself through persistence, political backing and an aggressive operational strategy.

Despite crude shortages, price wars, regulatory run-ins and lawsuits, the refinery has stabilised domestic supply, forced long-overdue market adjustments and compelled powerful players in the downstream sector to rethink their old models. Each confrontation tested the strength of the project and the resolve of its founder.

Yet, instead of retreating, Dangote doubled down, not only pushing ahead with production but also embarking on a massive expansion that signals confidence rather than fear.

The refinery may not yet have won the war, but it has survived its most turbulent phase and appears to be entering a more predictable terrain. Its success or otherwise will depend on how major stakeholders adjust to its growing dominance and how the government enforces policies to protect both consumers and local production.

But one thing is clear: most players in the industry are not opposed to the refinery; rather, everyone is fighting for survival — and that is where collaboration becomes critical.

As Adetunji Oyebanji of 11 Plc put it, all players want to recover their costs, which explains why it appears they are fighting Dangote.

For now, the battle seems to have subsided, but experts said it has not ended, especially as parties struggle for survival in an industry long ruled by ‘powerful’ stakeholders.

The BoG says this marks an improvement on the $5.57b surplus

The BoG says this marks an improvement on the $5.57b surplus

The ceremony was attended by District Chief Executives, the Regional Coordinating Director, Regional Directors of the Controller and Accountant General’s Department and the Youth Employment Agency, Municipal Coordinating Directors, heads of security agencies, as well as religious and traditional leaders.

The ceremony was attended by District Chief Executives, the Regional Coordinating Director, Regional Directors of the Controller and Accountant General’s Department and the Youth Employment Agency, Municipal Coordinating Directors, heads of security agencies, as well as religious and traditional leaders.

![Mahama pays courtesy visit to Kufuor [Pictures] Mahama pays courtesy visit to Kufuor [Pictures]](https://citinewsroom.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/589923698_18444853591101399_2725214060191230890_n.jpg)

More Photos

More Photos

“This morning a Police Patrol Squad came to town to fire warning shots. As I speak, two people have lost their lives. The community members have also blocked the road,” he said.

“This morning a Police Patrol Squad came to town to fire warning shots. As I speak, two people have lost their lives. The community members have also blocked the road,” he said.