Drug abuse, particularly among young people, is rapidly becoming one of Ghana’s most pressing public health emergencies. Over recent years, Ghana has experienced a dramatic rise in pharmaceutical drug misuse, especially tramadol, widely recognized on the streets as “Red” due to its distinctive high dose red tablets.

Although originally prescribed medically to treat moderate to severe pain, tramadol is now frequently misused by Ghanaian youths, commercial drivers, manual laborers, and students.

The crisis recently gained heightened attention due to the social media trend on X (formerly called, Twitter) known as “Wonnim Red” (“You don’t know Red”), a viral trend exposing and inadvertently glorifying the dangerous misuse of high dose tramadol. This trend sparked heated public debate and raised serious concerns about the integrity of Ghana’s pharmaceutical supply chain.

To contextualize this issue, Ghana does not domestically manufacture tramadol at the potency levels currently available on the streets. Nevertheless, variants with 120mg, 225mg, and even 500mg doses, substantially exceeding medical recommendations, are readily accessible. According to the Narcotics Control Commission (NACOC), tramadol is illegally imported primarily from India, China, and parts of the Middle East.

Traffickers exploit Ghana’s porous borders located predominantly in the Northern and Volta regions, with shipments frequently concealed within legitimate pharmaceutical products and food items, effectively bypassing port and customs inspections.

Given this alarming influx and recent surge, it is crucial to highlight the profound implications of tramadol abuse on individual health, societal stability, and national productivity.

Recent data illustrate a troubling prevalence of tramadol abuse across various demographics in Ghana. A study focusing on commercial drivers and their assistants within Accra indicated that approximately one quarter regularly misuse tramadol, primarily to maintain prolonged periods of alertness and productivity. Tramadol abuse extends beyond professional drivers, with similarly disturbing trends noted in urban informal settlements.

For example, approximately 43 percent of youths in these areas consume tramadol to enhance their energy for demanding physical labor. Alarmingly, more than half of these young individuals continue using tramadol despite experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms, highlighting the critical gaps in addiction awareness and management resources.

The motivations driving tramadol misuse in Ghana are complex. Economic pressures are significant contributors, particularly among the working class. Many young people believe tramadol enables them to engage in strenuous physical tasks for extended hours, while others claim it enhances sexual endurance (“medi ky3”).

Additionally, underlying mental health challenges such as stress, depression, and anxiety push many individuals toward substance abuse as a coping mechanism, due to the limited accessibility of mental healthcare in Ghana. Furthermore, social dynamics involving peer influence and viral social media trends contribute to tramadol’s allure, portraying the drug as socially acceptable or even desirable for asserting strength and social standing.

Beyond immediate psychoactive effects, tramadol misuse carries severe chronic health consequences. Long-term tramadol consumption significantly elevates the risk of cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, arrhythmias, and heart failure.

Chronic tramadol users also face increased susceptibility to liver damage, including liver toxicity and hepatic failure. Another critical health concern is respiratory depression, wherein prolonged high dose use impairs lung function, sometimes leading to life threatening respiratory distress or coma.

Mental health disorders, including psychosis, depression, anxiety disorders, and cognitive impairment, are also prevalent outcomes of chronic abuse. This spectrum of chronic health issues places substantial strain on Ghana’s already overburdened healthcare infrastructure.

In recognizing the urgency of this crisis, Ghanaian authorities have initiated multiple interventions aimed at reducing tramadol abuse. The Narcotics Control Commission has intensified its efforts, intercepting millions of illegally imported tramadol tablets at major entry points, particularly Tema Port.

Concurrently, law enforcement agencies, including the Ghana Police Service, have carried out raids in known drug hotspots such as Ashaiman, Kasoa, and Tamale, resulting in significant arrests and seizures. Additionally, national awareness campaigns by organizations like the Food and Drugs Authority (FDA) have educated young people about the severe dangers associated with tramadol misuse.

Despite these commendable efforts, substantial challenges persist. Ghana’s borders, particularly those in the Northern and Eastern regions, remain vulnerable, allowing continuous illegal entry of high dose tramadol from abroad. Further complicating the issue is corruption within the pharmaceutical supply chain, facilitating the diversion of prescription medications into unregulated markets.

Rehabilitation and addiction recovery services in Ghana remain markedly insufficient, leaving numerous addicts without adequate pathways to recovery. As a result, tramadol abuse continues largely unabated, impacting communities both socioeconomically and in terms of public health.

The emergence of the “Wonnim Red” social media trend, although problematic, has sparked positive responses from civil society. Initiatives such as the “Stop Red” campaign have gained momentum, utilizing these same digital platforms to counteract the dangerous glorification of drug abuse.

These campaigns actively engage influential figures and celebrities to disseminate compelling anti-drug messages, aiming to reshape public perceptions of substance misuse. Nonetheless, for these grassroots efforts to achieve lasting impacts, institutional support and sustainable funding are essential.

To effectively address the tramadol abuse crisis, we must strengthen border controls, improve detection technology at entry points, and foster regional collaboration among West African nations to disrupt illicit drug trade networks.

We also recommend enhanced regulatory oversight of pharmaceutical imports and rigorous monitoring of retail pharmacies to limit the availability of high dose tramadol.

Additionally, we strongly urge relevant stakeholders to significantly invest in addiction treatment centers, mental health services, and community based rehabilitation programs to support individuals battling drug dependence.

Furthermore, we advocate for educational institutions to integrate comprehensive drug awareness programs into curricula, ensuring early and continuous preventive education.

Ghana stands at a critical juncture in addressing drug abuse. A comprehensive and coordinated national response involving law enforcement, robust public health initiatives, and sustained educational efforts is essential.

The social and economic costs of inaction, measured in lost productivity, fractured families, and chronic health burdens, far outweigh the resources needed to combat this epidemic effectively.

Thus, it is imperative for government institutions, civil society groups, healthcare professionals, educators, and the broader public to unite in reclaiming Ghana’s youth from the devastating impacts of tramadol dependency, ensuring a healthier, more stable future for next generations.

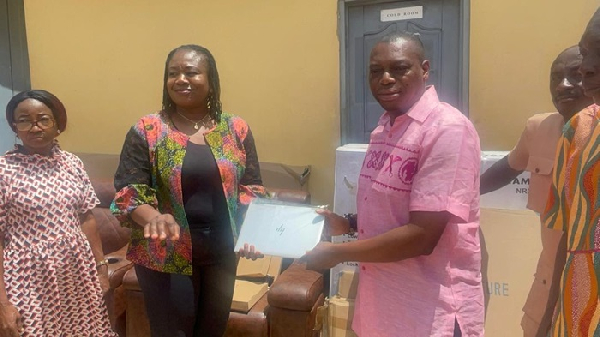

Prof Nyarko (in pink shirt) presenting laptop to Kwadaso Municipal Health Directorate officials

Prof Nyarko (in pink shirt) presenting laptop to Kwadaso Municipal Health Directorate officials