Abstract

The call for reparations for African nations subjected to centuries of colonial exploitation is steadily gaining traction within global socio-political and academic spheres. This paper presents an in-depth exploration of reparations using Ghana as a case study. Integrating a detailed historical backdrop, theoretical frameworks on justice and post-coloniality, and an evaluation of contemporary socio-economic realities, this study highlights the multivalent dimensions of reparations. Through a nuanced examination of stakeholder perspectives, political complexities, and pragmatic policy recommendations, this paper endeavours to offer a robust, globally relevant analysis while emphasising Ghana’s unique historical and cultural context as pivotal to understanding broader reparations discourse.

Introduction

The imprints of colonialism on African societies persist in multifarious economic, political, and cultural inequalities. Nowhere is this more salient than in the discourse surrounding reparations actions intended to redress historical injustices stemming from slavery, colonial economic exploitation, and cultural dislocation. Ghana, as the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence in 1957, symbolises both the triumph of decolonisation and the unresolved legacies of imperial domination.

Reparations debates evoke fundamental questions about justice and historical accountability. This paper situates Ghana at the intersection of these discourses. It proceeds through an integrated lens that combines historical context, empirical data, key theoretical insights, stakeholder viewpoints, policy discussions, challenges, and forward-looking considerations.

Specifically, this paper adopts restorative justice theory centred on healing and restitution (Zehr, 2002) and post-colonial theory, which unveils the continuing power dynamics rooted in colonial legacies (Said, 1978; Fanon, 1963). These theories underpin the case for reparations beyond mere monetary compensation, extending into realms of cultural recognition and institutional reform.

Historical Context: Ghana’s Colonial Legacy and Economic Exploitation

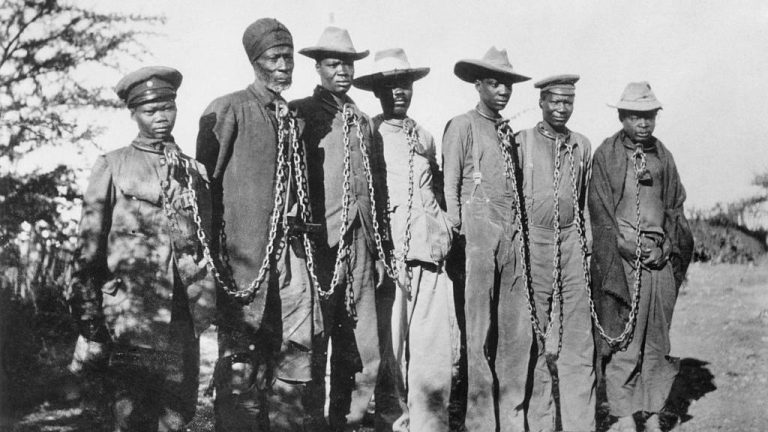

The colonial history of Ghana encompasses a rich yet turbulent narrative of African resilience amidst European imperial designs. Originally a series of wealthy and sophisticated Akan states, including the Asante Empire, Ghana was drawn into the transatlantic slave trade in the 15th century. Over three centuries, an estimated 12 million Africans were forcibly removed from West Africa, devastating societies and disrupting demographic balance (Eltis & Richardson, 2010).

With British colonisation in the late 19th century, Ghana’s economic structures were reoriented towards extractive industries. The colonial economy privileged gold mining and cocoa production, positioning Ghana as a centre for resource extraction for the enriching British Empire (Austin, 2005). The British introduced cash-crop monoculture, depreciating subsistence agriculture and leading to food insecurity (Berry, 1985).

Colonial policies also dismantled indigenous governance, introducing administrative hierarchies that privileged colonial authorities over traditional leaders. These disruptions undermined social cohesion and cultural institutions (Nkrumah, 1965). The resulting uneven economic development entrenched inequalities that persist, contributing to systemic poverty and hindering infrastructure growth decades after independence.

Empirical studies corroborate the profound economic void colonialism left behind. Ghana’s GDP per capita remains substantially lower than leading Western economies. A World Bank report from 2020 highlights that despite progressive economic reforms since independence, colonial patterns of resource dependency continue. The export of primary commodities, with vulnerable price fluctuations, constrains sustainable development (World Bank, 2020).

Case Study: Cocoa Economy and Labour Exploitation

The cocoa industry exemplifies the colonial exploitation legacy. Established under British tutelage in the early 20th century, cocoa generated wealth, mostly extracted by multinational corporations and colonial administrators (Hill, 1963). Cocoa farmers were often subject to harsh labour expectations, unfair pricing, and limited market agency. Post-independence Ghana has struggled to cease economic dependence on volatile commodity exports, evidencing a form of ‘neo-colonialism’ criticised by Kwame Nkrumah (1965).

Theoretical Framework: Justice, Reparations, and Post-Colonial Thought

Repairing the damages wrought by colonialism requires an integration of justice theories. Restorative justice, as described by Zehr (2002), aims to restore victims, address harms, and engage offenders in accountability principles applicable to international reparations. Distributive justice, particularly Rawlsian theory (1971), demands rectification of inequalities stemming from unjust origins.

Post-colonial theory compels us to consider power asymmetries that perpetuate colonial hierarchies beyond formal independence (Said, 1978; Fanon, 1963). This calls for reparations that do not merely accommodate economic redress but challenge structural inequities embedded in global politics, economics, and culture (Mamdani, 2008). Reparations in this optic involve symbolic recognition, restitution of cultural artefacts, and reform of institutional frameworks.

Empirical Evidence: Socio-Economic Impact and Statistical Overview

The economic impact of colonialism on Ghana is measurable and multifaceted. According to the World Bank (2020), Ghana’s per capita income in 2019 was approximately $2,200, compared to over $40,000 in the United Kingdom, a principal colonial power. The inequality index, measured by the Gini coefficient, hovered near 44, indicating significant income disparities. These statistics reflect structural barriers rooted in colonial economic arrangements (World Bank, 2020).

In education, while Ghana has made strides, literacy rates remain uneven, particularly in rural regions historically marginalised during colonial rule (UNESCO, 2018). Infrastructure disparities, such as roads, healthcare, and energy access, also disproportionately affect regions that were economically sidelined under colonial administration.

Reparations advocates argue that these enduring developmental deficits are reparable harms stemming from colonial extractive policies. A 2019 African Union report quantifies reparations owed to African nations collectively at approximately $777 trillion, an estimate encompassing resource drain, human capital loss, and debt accrued through unfair colonial treaties (African Union, 2019).

Stakeholder Perspectives: Diverse Voices in the Reparations Movement

Ghana’s reparations discourse is vibrant and multi-layered, reflected in the perspectives of politicians, academics, activist groups, and the diaspora.

Government: The Ghanaian government has publicly supported reparations claims, framing them as critical for rectifying historical economic imbalances and accelerating development (Ghana News Agency, 2021). President Nana Akufo-Addo has called for more robust international engagement on reparations, positioning Ghana as a moral leader.

Civil Society and Activists: Organisations such as the Pan-African Reparations Coalition demand reparations encompassing financial restitution and cultural recognition, spotlighting restitution of artefacts and reparative education on colonial legacies (Pan-African Reparations Coalition, 2022).

Academics and Intellectuals: Scholars emphasise the importance of reparations within a framework of transitional justice, advocating for reparations that strengthen institutions and challenge neo-colonial influences (Mamdani, 2016). Intellectuals such as Kwame Appiah stress the ethical dimension of reparations as a form of collective memory and humanity recognition (Appiah, 2006).

Ghanaian Diaspora: Members of the African diaspora have increasingly called for reparations, linking them to broader racial justice movements, notably in the United States and Europe (Cooper, 2020). Diaspora activism influences domestic discourse through advocacy and remittances.

Policy Recommendations: Strategic Approaches to Reparations

A constructive reparations agenda for Ghana requires multi-tiered strategies:

Establishment of a National Reparations Commission: A body mandated to assess reparations claims, oversee dialogue, and formulate coherent policy integrating economic, cultural, and educational reparations.

Creation of an International Reparations Fund: Mobilised through diplomatic negotiations with former colonial powers and international financial institutions. Funds would focus on infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

Legal Advocacy and International Law: Utilising international legal instruments such as the UN Human Rights framework to bolster reparations claims. Ghana could pursue cases or negotiations leveraging precedents from South African compensation schemes post-apartheid.

Cultural and Symbolic Reparations: Securing the return of artefacts, fostering public commemorations, and incorporating accurate colonial histories in education curricula, contributing to societal healing.

Economic Diversification and Development Partnerships: Using reparations to fund sustainable development projects, reducing resource dependence, and aligning with Ghana’s Vision 2020 plans.

Challenges and Counterarguments

Critics of reparations raise valid concerns requiring considered responses:

Feasibility: The huge scale of reparations claims often appears impractical. However, phased and targeted reparations programs render the challenge manageable, reflecting lessons from Germany’s reparations post-World War II.

Divisiveness: Reparations may exacerbate ethnic or social tensions. Ghana’s diverse society needs inclusive dialogue mechanisms to build collective consensus and avoid polarisation.

Accountability: Questions about who should pay reparations persist. In reality, responsibility falls on nation-states that benefited from colonialism, thus requiring diplomatic and legal engagement to define obligations.

Neo-Colonialism vs. Reparations: Some argue economic development is better achieved via current trade and investment rather than reparations. Nonetheless, reparations can be transformative by addressing structural inequities obstructing genuine economic emancipation.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Ghana stands at a critical juncture in the global reparations movement. Its historical experiences, socio-economic realities, and political will position it as a leader in demanding reparative justice. While challenges remain substantial, the multifaceted case for reparations grounded in ethical imperatives, empirical inequalities, and theoretical insights is compelling.

Future research should deepen the empirical linkage between colonial harms and contemporary disparities in Ghana. Comparative studies with nations that have successfully secured reparations or compensation would further inform strategy. Additionally, examining reparations’ long-term socio-political impact will strengthen advocacy and policy formulation.

Ultimately, reparations for Ghana are not a panacea but a necessary element in the broader project of decolonisation, healing, and equitable development. Through committed domestic and international engagement, reparations can catalyse transformative justice for Ghana and serve as a beacon for the continent.

About the Author:

Dominic Senayah, an International Relations Researcher who dives deep into the realms of Trade, Migration, and Diplomacy. With a rich background in Business Development and Marketing Communications, I bring a unique perspective to my analysis of global issues. My goal is to enrich academic discussions and enhance public understanding of the intricate dynamics that shape international relations discourse.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Myth 5: “If I do not have cash now, I have no choice but to miss the deal”

Myth 5: “If I do not have cash now, I have no choice but to miss the deal”

)

)

)

)