.

GoldBod. GoldBod. GoldBod.

This name keeps resurfacing for all the wrong reasons. Ghanaians were first invited to believe that this novel state-owned enterprise would work near-miracles for the cedi, Ghana’s reserves, and the gold value chain. Instead, what do we see? GoldBod has worsened the galamsey menace, and the IMF now confirms that it has generated financial losses of $214 million to the state. Beyond partisan ping-pong and performative defence, any serious citizen must be alarmed that this much-celebrated intervention has crossed the line from bold experimentation into institutional recklessness.

Is this part of the so-called “reset” scam sold to Ghanaians? A scandal of this magnitude demands accountability. The Governor of the Bank of Ghana must resign with immediate effect. If these figures reflect just nine months of operations under this so-called “galamsey board’s” operations, then one must ask—how much worse could the damage be by the time this NDC government leaves office in the next three years?

The losses are real. This is government-provided data—not conjecture, not opposition propaganda, and certainly not figures pulled out of thin air. Just as GoldBod is quick to claim credit for any positive forex-related development in the economy, these losses cannot be dismissed as “speculative.” For months, stakeholders demanded granular information on pricing, volumes, fees, and counterparties. That data was consistently withheld. Yet it somehow existed in sufficient detail to be submitted to the IMF. Now, the IMF has confirmed what concerned citizens have been saying all along.

If we are expected to distrust the IMF on these losses—despite the fact that it obtained its data directly from the government—then why should Ghanaians trust anything else the IMF reports, including claims that the economy is recovering? Should the positive assessments be discounted too? Transparency cannot be selective.

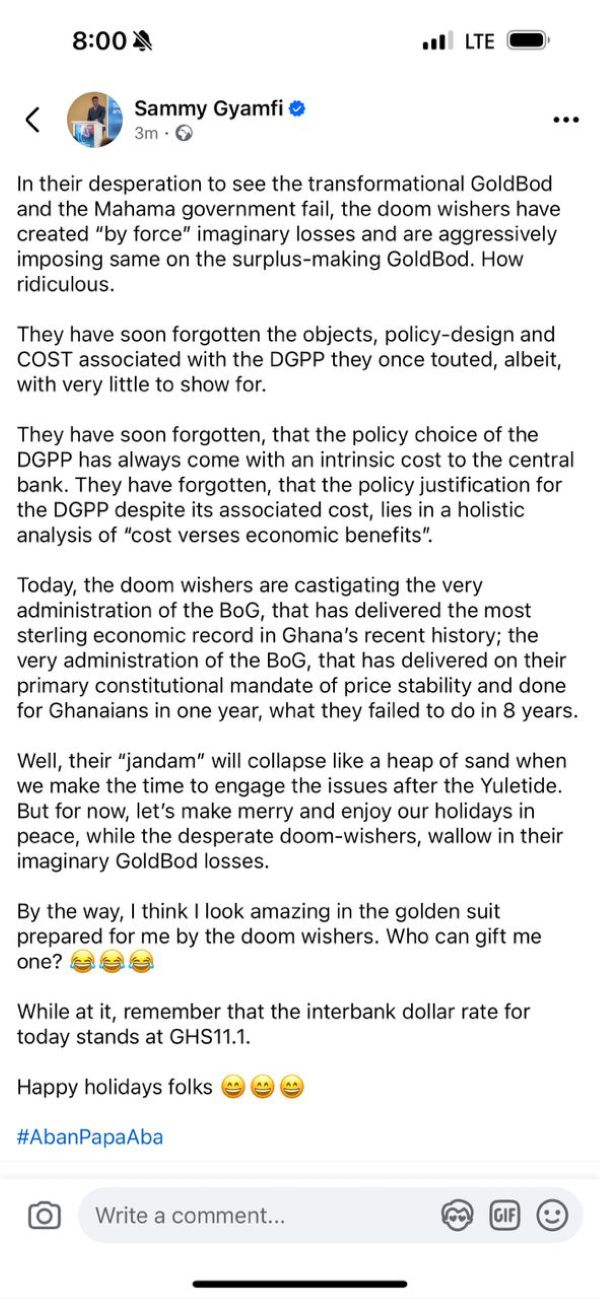

Anyone who follows the sequence of the NDC’s arguments will recognize the pattern. When facts become inconvenient, the response is often audacity masked as ignorance—clouding evidence to manufacture narratives that serve propaganda rather than truth.

True to its track record, the NDC government is now attempting to conceal these losses on the monetary side—burying them on the books of the Bank of Ghana so they can be treated as routine trading losses of the central bank. Ghanaians have seen this before. Prior to 2017, SOE debts were deliberately hidden off the central government’s books to understate public debt. Eventually, those liabilities crystallised—compounded by COVID—and the NPP government was forced to absorb them, contributing significantly to the depth of the DDEP.

GoldBod has now emerged as an SOE with a larger-than-average systemic fiscal risk, and the IMF is right to sound the alarm early, before it becomes another energy-sector-style catastrophe that Ghanaians will pay for over decades.

How GoldBod Operates

To understand the source of these losses, it is necessary to examine GoldBod’s operations:

When the Ghana Gold Board was established, it was intended to act as the sole buyer and exporter of gold from the small-scale mining sector, financed through a $279 million revolving fund announced in the 2025 Budget. That model has since collapsed. By September 2025, the budgeted funds had not been released. GoldBod now functions primarily as an intermediary—collecting funds for gold purchases on behalf of clients, including the Bank of Ghana, and earning income through service charges and assay fees.

In practice, this arrangement places the Bank of Ghana at the center of GoldBod’s financing. The central bank supports operations through two main channels:

1. By collecting cedis from commercial banks, forwarding them to GoldBod to purchase gold from small-scale miners, and later reclaiming the dollar proceeds to supply foreign exchange to the same banks.

2. By using high-powered money to purchase gold directly from GoldBod, which is either sold on the international market or refined into Ghana’s reserves.

The losses arise primarily from pricing distortions. GoldBod buys gold at international market prices—sometimes even at a premium to discourage smuggling—but sells unrefined gold at a discount to cover refining, transport, assay, and financing costs. In October 2025, for instance, the world price of gold averaged $4,054 per ounce, yet Ghana realised only $3,919 per ounce—a shortfall of about $135 per ounce, or 3%.

This outcome completely contradicts the original logic of the GoldBod model. Gold was supposed to be purchased at a discount so that fees and margins would cover costs. Buying at a premium and selling at a discount is mathematically indefensible. So, under the current structure, GoldBod collects profits while the Bank of Ghana absorbs both trading losses and balance-sheet risk.

Accountability Is Non-Negotiable: The BoG Governor Must Go!

At this point, accountability is no longer a matter of debate; it is an obligation. Hundreds of millions of dollars in losses have been absorbed by the Bank of Ghana, while GoldBod records profits from the very same transactions. This is not an accounting anomaly; it is a structural failure deliberately embedded in the programme’s design. And it has all happened under Governor Asiama’s watch.

When a state-backed intervention systematically transfers risk from a state-owned enterprise onto the central bank’s balance sheet, responsibility rests squarely with the Governor. Under Ghana’s legal and institutional framework, the Governor of the Bank of Ghana is not a ceremonial figure. He is the final custodian of the Bank’s balance sheet, the guardian of monetary credibility, and the ultimate authority over quasi-fiscal operations. He cannot plead ignorance, outsource blame, or distance himself from outcomes executed under his watch.

This is not a minor error of judgment. It is a sustained policy choice that has inflicted material losses on the state. In any serious jurisdiction, such a failure would trigger immediate resignation. Anything less sends a dangerous signal—that public institutions may gamble with national finances without consequence.

Resignation is therefore the minimum standard of institutional accountability.

Legal Scrutiny Is Inevitable — Mr Attorney-General, Silence Is Complicity

Beyond resignation lies a constitutional obligation for legal scrutiny.

The Attorney-General cannot avert his gaze. The IMF report—based on data supplied directly by the Bank of Ghana—confirms losses that are real, quantified, and avoidable. These are not market shocks or acts of God; they are the foreseeable outcome of a flawed pricing model and weak oversight. Where public officials authorize or tolerate arrangements that impose avoidable losses on the state, the law is not optional.

Quasi-fiscal operations that quietly bleed the central bank while insulating an SOE from risk raise fundamental questions of fiduciary duty, abuse of discretion, and financial mismanagement. The Constitution does not permit such losses to be waved away as technicalities. Nor does it allow accountability to be suspended for political convenience.

The Attorney-General must therefore investigate and prosecute those responsible. If this were about the habitual persecution of political opponents, we would by now have seen the familiar spectacle of hurried press conferences and hollow media theatrics. Yet he is quiet on this matter.

Silence, in this context, is not neutrality. It is complicity.

If the Attorney-General is serious about protecting the public purse, investigations must commence immediately, followed by prosecutions where the evidence leads. Ghana has paid too high a price for a culture in which officials deny obvious failures today, only to admit them years later when the damage is irreversible. This moment demands a clean break from that tradition.

The Time for Action is Now

Ghana cannot afford another round of polite denials or political theatrics. The facts are undeniable: the GoldBod programme has generated hundreds of millions in losses, borne by the state. The Governor of the Bank of Ghana cannot escape responsibility. Leadership that allows such a misalignment of risk and reward is institutionally reckless.

The Attorney-General also has no room for inaction. Where fiduciary duty has been breached or oversight neglected, the law must follow. Accountability is not a political gesture, it is the only mechanism to restore public confidence.

Beyond individuals, systemic reform is urgent. GoldBod’s model—buying at a premium, selling at a discount, and shifting the burden to the central bank—cannot continue. Seed capital without structural reform amplifies risk: losses will compound, capital will erode, and the state will bear the fallout again. Transparent pricing, rigorous internal controls, and clear fiscal responsibility are essential to prevent repeating SOE mistakes.

Ghana deserves economic management that is truthful, accountable, and sustainable. GoldBod may yet play a constructive role in the national gold value chain, but success requires honesty, transparency, and leadership willing to confront inconvenient truths and to be accountable to the people. The alternative is a financial and institutional crisis that Ghana cannot afford.

The choice is now stark: accept responsibility, submit to scrutiny, and reform—or compound the damage and drag the state deeper into another preventable crisis.