Introduction

Recent events at Wesley Girls Senior High School, Cape Coast, have reopened a long-standing public debate in Ghana about the relationship between denominational identity and institutional practice, specifically the extent to which mission schools may restrict or regulate non-Christian/Muslim religious practice on their campuses.

In late 2024 and through 2025 a legal challenge brought against Wesley Girls alleging restrictions on Muslim students’ ability to observe religious duties generated national commentary and formal litigation, prompting intervention by the Methodist Church and responses from civil society (MyJoyOnline, 2025; GhanaWeb, 2025).

The case exposed not merely an isolated dispute; it revealed a recurring tension: how to balance the historic ethos of mission-founded schools with constitutional guarantees of religious freedom and the reality of plural student populations.

This tension is not unique to Ghana. Debates over religious accommodation in denominational schools have surfaced across Africa and in other regions. Academic discussion about rights, institutional autonomy, and state neutrality in religious education appears in comparative literature and jurisprudence (Owusu-Ansah, 2016; Hinds, 2024).

Countries with strong denominational schooling traditions, for example, parts of East Africa and the Republic of Ireland, frequently wrestle with questions of accommodation, admission, and the content of school life when student bodies become religiously diverse (Ipgrave, 2010; Lenta, 2008).

In the specific case of Ghana, and indeed in several other countries, each resurgence of this controversy is shaped by a recurring argument from the mission-assisted schools. They frequently assert that their consistent academic performance is rooted in what they describe as “mission values”, and that allowing students of other faiths to fully manifest their religious obligations will dilute these values. According to this view, such dilution will weaken the ethos of the school and, by implication, erode the academic standards for which these institutions are known.

The Wesley Girls episode is therefore an entry point: it invites us to reconsider a deeper, perennial claim advanced by many mission schools and their defenders, namely the claim that “mission values” – religious ritual, devotional life, moral instruction — are the principal cause of superior academic performance.

The purpose of this article is not to adjudicate the legality of whether mission-assisted schools should permit students of other faiths to manifest their religious practices. Rather, the article seeks to empirically and critically evaluate the central claim that mission values are the principal factors underpinning academic excellence in mission-assisted schools, and that any perceived dilution of these values would undermine both academic and holistic performance.

The paper begins in Ghana, where mission schools, commonly referred to as mission-assisted schools because of the governmental support they receive, constitute a significant share of schools from the basic through the secondary to the tertiary levels of education.

The analysis then expands its scope to Africa and beyond, drawing on empirical data and comparative international evidence to evaluate the central supposition. The argument moves from historical description to analytical critique and culminates in a set of recommendations for research and policy.

Purpose and Scope

In public debates, mission schools often defend particular school practices by invoking the argument of “mission values.” The implicit causal story runs as follows: the religious ethos nurtured by mission founders instils discipline, self-control, and moral purpose; these virtues translate into punctuality, study habits, and an orderly culture; such culture produces superior academic outcomes. A corollary is then advanced: permitting other faiths to openly observe their practices will dilute the mission ethos, and hence degrade academic performance.

This article contests that causal chain. It does so by (1) tracing the historical record of mission school performance in Ghana; (2) interrogating the mechanism proposed by defenders of the claim; (3) assembling cross-level evidence from basic, secondary, and tertiary education in Ghana and from African and international literatures; and (4) offering a logically tight conclusion grounded in empirical research.

The writer does not dispute that school culture, which can be nurtured without mission values, contributes to holistic school performance. The argument departs only from the claim that mission values are the primary factor explaining such performance, and that their perceived dilution spells doom for holistic school performance.

The history of academic performance in mission schools, Ghana

Christian missions played a foundational role in the development of formal schooling in the Gold Coast and later Ghana. From the nineteenth century, denominational actors established primary, middle and secondary institutions; notable examples include Mfantsipim (Methodist, 1876), Achimota (colonial-state but mission-era legacy), Adisadel College and others (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2017; IOE, 2023).

Elite mission secondary schools acquired high public profiles not solely as a result of their consistent academic performance, but because of historical advantages and institutional factors.

As some of the earliest established secondary schools in Ghana, they attracted the top available students, benefiting from selective admissions, strong community endorsement, and access to superior resources.

This created a virtuous cycle in which high-calibre students enhanced school performance, which in turn reinforced the institution’s prestige (IOE, 2023; Awedoba, 2018). Only later did their academic excellence become a widely recognized measure of reputation.

The historical and empirical evidence above show that the academic excellence of mission-assisted schools in Ghana stemmed primarily from institutional and structural factors, including early establishment, selective student intake, quality teaching, governance, and resources, rather than mission values alone. While school culture contributes, it is not sufficient to explain performance.

Tackling the Main argument: why “mission values” alone cannot explain excellence

The article now establishes the central claim: mission values are neither necessary nor sufficient as a primary driver of academic excellence. I develop this claim across three tiers of education: basic, secondary, and tertiary.

1. Senior high/secondary schools: Ghana, then Africa, then comparative perspective

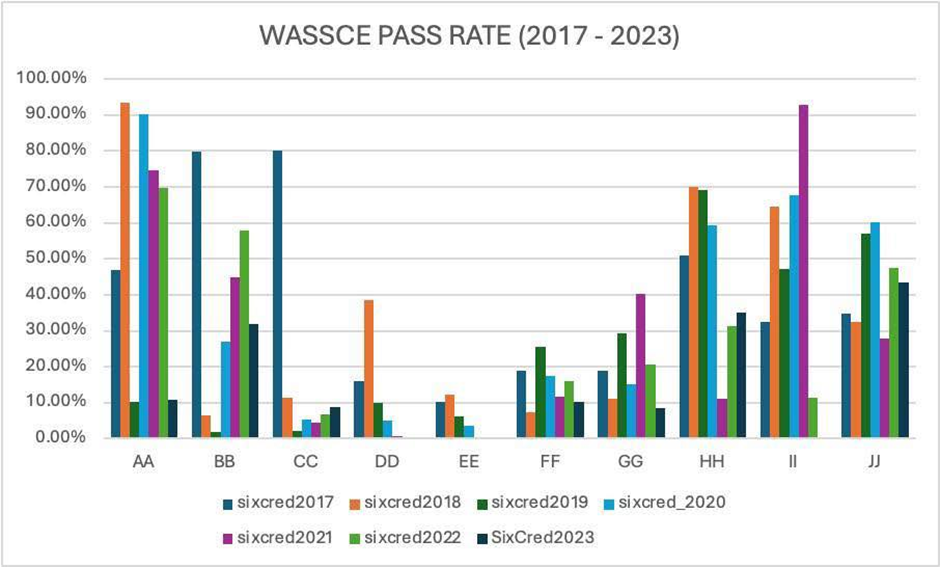

Ghana. At the secondary level, the empirical pattern is twofold. First, many mission-heritage secondary schools perform strongly in national examinations; second, other government-run schools, and an increasing number of non-mission private schools, also achieve top results. Close examination shows that institutional qualities, not doctrinal practice, explain performance.

Research on school effectiveness in sub-Saharan contexts identifies teacher quality, instructional time, school leadership, school resources, and pupil selection as the primary determinants of academic outcomes (Azigwe, 2016; EDQUAL, 2006).

In Ghana, the reputation of elite mission schools derives substantially from historical legacy, selective intake, and the mobilisation of alumni and state resources; many of these schools now operate effectively as public institutions with government funding and oversight (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2017).

Selection is central: high-performing SHSs attract and admit the top cohort of BECE candidates, that prior achievement predicts later success. Thus the “school effect” often observed is confounded with student intake quality. The empirical literature on school quality and admissions confirms that selective intake explains a large share of variance in secondary outcomes (Ajayi et al., 2014; EDQUAL working papers).

Important examples of high-performing purely government-run schools, which challenge a simple religion-to-results explanation, include public SHSs that have matched or exceeded mission-heritage schools in specific years and districts. Comparative studies and national performance data show variations in outcomes that align more closely with resource availability and governance quality than with denominational status (Atuahene et al., 2019; SCIRP, 2023).

NSMQ records further complicate the mission-values thesis: notably, no all-girls mission-assisted school has ever won the National Science and Maths Quiz, and finalists and winners include both mission-heritage and non-denominational schools, which indicates that denominational origin is neither necessary nor sufficient for success (NSMQ archive, 1994–2025).

Three related facts sharpen the interpretation. First, many mission-heritage secondary schools benefited historically from first-mover advantages and selective intake, which concentrated top candidates and helped establish early reputations.

Second, the introduction of the Computerised School Selection and Placement System in 2005 substantially curtailed discretionary, school-level selection power and redistributed top candidates more widely; stakeholders and policy reviews attribute shifts in traditional performance hierarchies, in part, to this reform (CSSPS policy documents; stakeholder analyses, 2005–2020).

Third, even with selective intake, mission-heritage schools continue to produce students who fail national examinations, which demonstrates that mission values alone cannot account for uniformly high outcomes; variations in student preparation, teacher quality, and resourcing remain decisive (SACMEQ; UWEZO).

Africa. The pattern replicates across the continent. SACMEQ and UWEZO assessments point to teacher presence, instructional methods, learning materials, and socio-economic background as primary predictors of learning outcomes in primary and secondary cycles (SACMEQ IV, 2019; UWEZO, 2015).

In contexts such as Kenya and Uganda, elite mission secondary schools do top national rankings, yet rigorous analyses attribute these outcomes to admission selectivity, urban location, teacher quality, and alumni support rather than to liturgical practice.

Low-fee private and well-resourced secular schools produce comparable or superior outcomes in many districts (Mugo, 2015; SACMEQ, 2019).

Global/Comparative. Internationally, the best-performing universities and secondary systems are not religiously dominated. Where denominational schools perform strongly, they often do so because of sustained funding, competitive admissions, and strong governance rather than confessional instruction.

Comparative education literature affirms that governance, resourcing and human capital are dominant predictors of school outcomes in diverse national settings (World Bank, various country reports).

Collectively, these findings undermine the claim that mission devotional life is the proximate cause of academic excellence at the secondary level. Mission schools often embed management cultures conducive to order, but secular institutions with equivalent management, resource endowments, and student selection achieve the same ends.

2. Basic / primary schools: Ghana evidence and wider African comparisons

At the basic level, the evidence is unambiguous. In Ghana and many African countries, private basic schools — secular or otherwise — frequently outperform mission-assisted public basic schools on standardized assessments.

District-level comparisons find that private primary/basic schools post higher BECE/KCPE proxies and learning outcomes, even where private schools deploy less formally trained teachers; the driving factors are supervision, school time usage, closely monitored instruction, and parental involvement (Atuahene et al., 2019; SCIRP, 2023; UWEZO, 2015).

SACMEQ analyses across southern and eastern Africa show that after controlling for socio-economic status and resource inputs, religious ownership is not a statistically significant predictor of primary reading and numeracy outcomes (SACMEQ IV, 2019). In short, denominational affiliation at the primary level does not confer an academic advantage; instead, managerial practices, accountable teacher deployment, instructional materials, and parental investment explain differences.

This finding is especially damaging to the “mission values” thesis. If moral-religious instruction were the secret of scholastic success, mission primary schools — which historically emphasized moral instruction — should outperform secular private counterparts. They do not.

3. Tertiary level: teacher training colleges, universities, and the decisive test

If mission values were genuinely responsible for educational excellence, that effect should persist into higher education. Yet tertiary determinants are emphatically secular and institutional.

Empirical analyses of university quality in Ghana and across Africa identify faculty qualifications, research intensity, library and laboratory infrastructure, governance, funding, and staff-student ratios as the core drivers of program quality and graduate outcomes (Opare, 2021; Esseh et al., 2025).

The highest ranked African universities — public or private — gain their standing through sustained investment in human capital, research output, and industry linkages. Religious affiliation of an institution is neither necessary nor sufficient for superior tertiary outcomes.

Teacher training colleges likewise show that inputs in teacher education, curriculum rigor, practicum quality, mentorship are decisive; denominational administration does not provide a reliable performance premium once inputs are controlled (SACMEQ country analyses; Azigwe, 2016).

The tertiary evidence thus constitutes the decisive test: mission status does not explain academic excellence at this level.

What the evidence and logic together show:

The claim that mission values are the primary determinant of academic excellence and that their purported dilution will lead to poor performance of assisted-mission schools collapses under the weight of empirical evidence and basic causal logic. There are three complementary reasons.

First, the historical success of elite mission secondary schools is almost always accompanied by structural advantages: early foundation, admission selectivity, endowments, urban location, alumni networks and, often, state funding. These variables produce measurable benefits for teaching and learning.

Second, the correlation between mission identity and discipline is real, but correlation does not establish causation: discipline can be produced by managerial systems, rules, and accountability mechanisms that are entirely secular. Private basic secular schools replicate or exceed these mechanisms.

Third, cross-level and cross-national data show that at the primary level mission schools do not generally outperform, and at the tertiary level mission affiliation is not predictive of superior outcomes. That pattern is inconsistent with a general causal claim that religious ethos is the main explanatory factor.

Policy and Research Implications

If policymakers and education stakeholders wish to raise learning outcomes, the evidence points to concrete levers: strengthen teacher training and accountability, improve instructional time and supervision, ensure adequate learning materials, support meritocratic and transparent admission processes where selection is used, and modernize governance structures so that alumni networks translate into recurrent funding for instruction rather than mere prestige (SACMEQ IV, 2019; UWEZO, 2015; Azigwe, 2016).

For researchers, the urgent task is to disentangle selection and institutional effects through matched-cohort designs and quasi-experimental methods, and to develop EMIS datasets that record school founding origins and governance models so that “mission origin” can be treated as an analyzable covariate rather than a cultural label.

Conclusion

Mission schools have a strong academic reputation because of their long history, and this reputation still influences how parents, students, and society view them. This image, shaped mostly by their academic performance, is not the result of students participating in routine denominational rituals.

Across basic, secondary and tertiary levels, the dominant drivers of scholastic outcomes are structural: human capital in the form of teachers and faculty, institutional resources, governance and leadership, student selection and socio-economic context.

Mission values may shape school ethos and contribute to non-academic goods, but they do not substitute for the concrete inputs and management practices that produce measurable learning outcomes.

Public discussions on this matter should therefore move beyond symbolic appeals to mission identity and focus instead on the managerial, operational and material determinants that reliably raise quality.

References

Adu-Gyamfi, S., Donkoh, W. J., & Addo, A. (2017). Educational Reforms in Ghana: Past and Present. [Institute of Education, University of Cape Coast].

Azigwe, J. B. (2016). The impact of effective teaching characteristics on student achievement in mathematics in Ghana. International Journal of Educational Research.

Atuahene, S., Kong, Y., Bentum-Micah, G., & Owusu-Ansah, P. (2019). The Assessment of the Performance of Public Basic Schools and Private Basic Schools, Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice.

EDQUAL (2006). Research Evidence of School Effectiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa. EDQUAL Working Papers.

Esseh, S. S., Ry-Kottoh, L. A., & Deny o, M. M. (2025). Examining Service Quality in Ghanaian Higher Education: A Comparative Analysis of Private and Public Universities. Journal of Higher Education Studies.

GhanaWeb. (2025, November). Methodist Church responds to Supreme Court case involving Wesley Girls High School. Retrieved from GhanaWeb.

Hinds, H. (2024). Protecting Muslim Students in Public Schools: Case Lessons and Legal Remedies. Public Interest Law Review.

Ipgrave, J. (2010). Including the religious viewpoints and experiences of faith learners. Comparative Education Review.

IOE, UCC. (2023). The Missionary Era and Educational Development. Institute of Education curriculum materials.

Mugo, J. K. (2015). A Call to Learning Focus in East Africa: UWEZO’s Measurement of Learning. Africa Education Review.

MyJoyOnline. (2025, November). Methodist Church Ghana responds to Supreme Court suit over Wesley Girls’ High School. Retrieved from MyJoyOnline.

Opare, E. (2021). Class Size, Teaching Quality and Student Outcomes: The Case of Ashesi University. Master’s Thesis, Ashesi University.

Owusu-Ansah, D. (2016). Secular Education for Muslim Students at Government-Assisted Christian Schools: Joining the Debate on Students’ Rights in Ghana. Journal of Islamic Studies and Culture.

SACMEQ. (2019). SACMEQ IV Final Report: Conditions of Schooling and the Quality of Education. Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality.

SCIRP. (2023). Exploring the Difference in Academic Performance between Private and Public schools: Teacher professional practice and resource endowment. Scientific Research Publishing.

UWEZO/Twaweza. (2015). Are Our Children Learning? UWEZO East Africa Report.

World Bank. Various country education sector reports.

By: Paul Ayiku