For more than two decades, Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) has been a beacon of social protection, ensuring that millions of citizens access basic healthcare without facing financial catastrophe. Yet, beneath this achievement lies a growing cancer that threatens the very survival of the Scheme — fraud and abuse.

Fraud and abuse (F&A) in health insurance are not abstract terms; they represent the deliberate or careless actions that siphon scarce funds away from genuine patients into undeserving hands. The World Health Organisation describes healthcare fraud as “the last great unreduced healthcare cost.” Globally, about seven percent of total health spending — nearly 500 billion US dollars annually — is lost to fraudulent claims and waste.

In Ghana, conservative estimates suggest annual losses of around 500 million dollars due to irregularities, inflated billing, and false claims.

Understanding the Problem

Fraud involves deliberate deception for financial gain, such as billing for services never rendered. Abuse, on the other hand, includes practices inconsistent with accepted medical or business standards, such as unnecessary tests or overprescription of medicines. While fraud is a criminal act, abuse — though less intentional — equally drains resources and undermines efficiency.

At its core, both acts share a single motive: financial gain. When healthcare providers, members, or even insiders at the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) exploit systemic weaknesses for profit, the Scheme’s integrity is compromised.

Why Fraud Happens

Several theoretical frameworks shed light on why people commit fraud. Donald Cressey’s Fraud Triangle points to three main factors: pressure, opportunity, and rationalisation. David Wolfe and Dana Hermanson later expanded this into the Fraud Diamond, adding capability as a critical element. In Ghana’s context, the NHIS’s design weaknesses — such as poor referral systems, weak credentialing, delayed payments, and manual claims processing — create fertile ground for these opportunities.

Additionally, misconceptions about insurance being “free money” and the perception that “no one gets punished” encourage unethical practices. When rules are loosely enforced, even honest professionals can be tempted to bend them.

How It Happens

Fraud and abuse occur at every level of the system:

– Providers: Phantom billing, upcoding, double billing, falsifying diagnoses, or unbundling services already covered under one tariff.

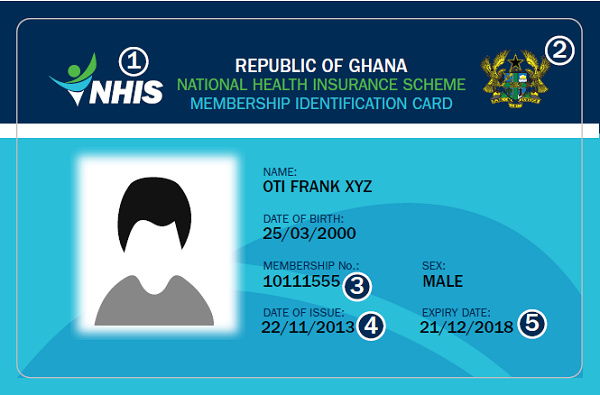

– Members: “Provider shopping,” card sharing, and impersonation — where one person uses another’s NHIS card.

– NHIA staff: Collusion with providers, selective vetting, or fast-tracking payments for personal gain.

Such acts not only waste money but also undermine trust between patients, providers, and the NHIA.

The Real-World Impact

The financial losses are staggering, but the hidden costs are even worse. Funds that could build clinics, supply essential medicines, or expand coverage are instead used to pay fraudulent claims. Over time, the Scheme becomes financially strained, leading to delays in reimbursement, reduced provider confidence, and — ultimately — poorer quality of care for patients.

Fraud and abuse also breed moral hazard. When both providers and clients perceive that wrongdoing goes unpunished, unethical behaviour becomes normalised. Trust — the foundation of any insurance system — is eroded, and public confidence declines.

What Must Be Done

The total elimination of fraud and abuse may be impossible, but minimising them is essential. As a guiding principle, “Integre Procedamus” — let us proceed with integrity — must underpin all actions of the NHIA, healthcare providers, and members alike.

1. Education and Continuous Training: Many infractions arise from ignorance. The NHIA, professional bodies, and civil society should invest in continuous education for providers, NHIS staff, and members on what constitutes fraud and its consequences.

2. Robust Information Systems: Digitising the claims process, integrating biometric verification at points of service, and using data analytics to flag outlier claims are critical. Electronic vetting systems have already proven more accurate and efficient than paper-based reviews.

3. Transparent Credentialing and Audits: Credentialing of health facilities must be free of favouritism or “fast-tracking” for monetary gain. Regular clinical audits should rely on clear benchmarks published in NHIS Statistical Bulletins to detect anomalies early.

4. Prompt Reimbursement and Tariff Reviews: Delayed payments and outdated tariffs create frustration and incentives for providers to charge illegal out-of-pocket fees. Timely reimbursement builds trust and discourages unethical shortcuts.

5. Establishment of an Anti-Fraud Department: The NHIA should establish a dedicated Fraud Prevention, Detection, and Mitigation Unit staffed by trained Accredited Health Fraud Investigators. Proactive monitoring — not reactive “pay and chase” recovery — is key.

6. Legal Reforms and Enforcement: Ghana urgently needs a law that explicitly criminalises health insurance fraud, similar to the U.S. Federal Health Care Fraud Statute. Offenders must face meaningful penalties to serve as a deterrent.

The Way Forward

Ghana has only recorded one major conviction for NHIS-related fraud — the case of Dr NK Ametewae and his nephew, who were sentenced to 10 and 5 years respectively for duplicating claims. The rarity of such prosecutions highlights the weakness of enforcement.

To safeguard the NHIS’s future, Ghana must combine strong legal action, technological vigilance, and ethical renewal. Collaboration between the NHIA, health professional councils, and law enforcement agencies is vital.

Civil society groups can also play a watchdog role, forming a coalition similar to the US National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association (NHCAA) to champion integrity and transparency in healthcare financing.

Conclusion

The NHIS remains one of Ghana’s proudest social protection achievements. But unless fraud and abuse are decisively addressed, the Scheme risks losing its credibility and sustainability.

Every cedi lost to fraudulent claims is a cedi denied to a sick child, a pregnant woman, or a poor farmer seeking care. It is time to act — not with fear, but with firm resolve and national pride.

Let us proceed with integrity — for the survival of the NHIS and the health of our nation.