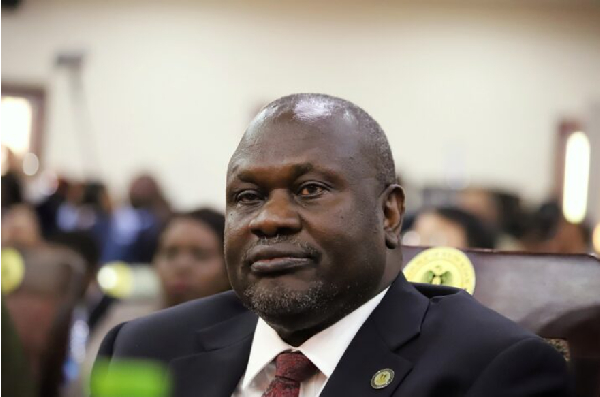

Riek Machar, South Sudan First Vice President

Riek Machar, South Sudan First Vice President

The trial of South Sudan’s suspended First Vice President, Riek Machar, opened on Monday in Juba under heavy security and restricted access.

Private media outlets, victims’ families, and members of civil society were barred from entering Freedom Hall, where the hearings are being held. Roads leading to the venue — including University of Juba Road, Custom Road, Ministries Road, and Hai Soura Road — were sealed off, causing major traffic disruptions in the capital.

The daughter of the late Gen David Majur Dak, killed in the Nasir attack at the centre of the case, criticised the restrictions.

“Denying access to victims’ families during the hearing makes no sense. Who, then, is justice being sought for? Justice that cannot be witnessed by the living is an empty ritual. Justice belongs not to the dead,” Abul Dak wrote on social media.

“They have already borne the weight of loss. But to the living who carry the pain, the memory, and the demand for truth. To exclude them is to silence the very voices that give justice its meaning,” she said.

The Union of Journalists of South Sudan (Ujoss) condemned the exclusion of private media, saying it violates press freedom as enshrined in the country’s constitution. Only State-owned South Sudan Broadcasting Corporation (SSBC) journalists were allowed to cover the session.

“The denial of access to the court for journalists is a direct attack on press freedom, as enshrined in Articles 24 and 32 of the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan (2011, as amended). Ujoss unequivocally condemns this act—especially when the restriction is enforced by the very institution tasked with upholding the constitution,” Ujoss chairperson Charles Patrick Oyet said in a statement.

Rights groups also questioned the transparency of the proceedings. Edmond Yakani, Executive Director of the Community Empowerment for Progress Organisation (Cepo), warned that excluding private media raises doubts about judicial independence and credibility.

Freedom Hall, ironically, is a symbol of South Sudan’s struggle for independence. It has over the years hosted key political events — including peace talks, consultations, and agreements between South Sudanese leaders and international mediators during the 21-year war with the North.

Dr Machar and seven of his Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) leaders — including former Petroleum Minister Puot Kang Chol and Deputy Chief of Staff Gen Gabriel Duop Lam — face charges of treason, murder, conspiracy against the State, and crimes against humanity.

The case stems from a March 2025 attack on a military base in Nasir, Upper Nile State, which the government says killed more than 250 soldiers and Gen Adak. Authorities accuse Machar of ordering the assault. He denies the charges, calling the proceedings politically motivated.

Machar has been under house arrest since March 26. His suspension last week by President Salva Kiir has been condemned by his party as a violation of the 2018 Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), which outlines power-sharing and transitional government structures.

Court session

The court session at Freedom Hall was presided over by a three-judge panel: James Alala, Stephen Simon, and Isaac Four.

Machar’s lawyers, led by former Court of Appeal justice Dr Geri Raimondo and senior advocate Kur Lual, argued that the special court lacked jurisdiction. They said the 2018 peace deal requires such cases to be tried by a Hybrid Court, not a domestic tribunal.

The prosecution, led by lawyer Ajo Noel Julius, countered that the special court has full constitutional authority, citing the gravity of the crimes and their impact on national security.

The judges directed the prosecution to share case files with the defence. The hearing was adjourned to Tuesday to allow the defence time to review the documents.

Machar’s bodyguard dies

The trial opened just days after the death of Captain Luka Gathok Nyuon, a close bodyguard of Machar, who died in detention at Jamus military facility in Juba. Nyuon had been held since March, shortly after Machar’s arrest.

As hearings resume, attention will focus on whether the special court can retain jurisdiction and whether access for the public and independent media will be restored — a test of South Sudan’s commitment to justice, transparency, and the 2018 peace deal.