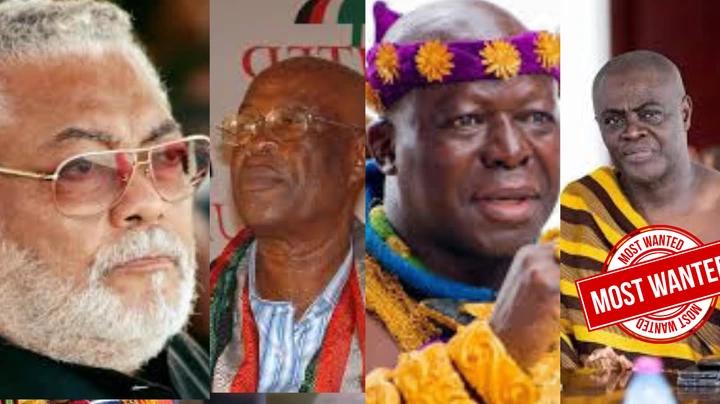

Otumfuo Osei Tutu II has once again asserted his authority over the Bono region, delivering a strong historical lesson to Dormaahene Osagyefo Oseadeeyo Agyeman Badu II. During a meeting with his elders, Otumfuo warned Dormaahene against undermining his influence, emphasizing that the Bono community has long been under Asante jurisdiction.

Otumfuo traced the historical ties between the Ashanti Kingdom and Bono, referencing key moments in Ghana’s political history. He stated that even former President Jerry John Rawlings was aware of Bono’s allegiance to Asante. According to Otumfuo, in 1985, Rawlings established a committee to address chieftaincy matters, followed by another committee in 1986 under Idrissu Mahama. Otumfuo claimed that Mahama later wrote a letter acknowledging that Bono lands belonged to Asante and invited the Asantehene to formally integrate them.

Further reinforcing his argument, Otumfuo recalled a past dispute where the Techiman chief contested his authority but ultimately lost. He warned Dormaahene to tread carefully, implying that history and tradition would not favor any attempt to challenge Asante’s dominance.

Otumfuo also listed several towns he claims belong to Asante, including Sampa, Kwantwuma, Bedu, Odumasi Number One, Akroso, and Bono. His remarks have reignited discussions about the historical relationship between Asante and Bono, with some traditional leaders supporting his stance while others advocate for greater autonomy.

Dormaa’s response to Otumfuo’s claims has been swift and defiant. Dormaahene has publicly rejected Otumfuo’s assertions, arguing that Bono chiefs have long maintained their independence and do not owe allegiance to the Ashanti Kingdom. He has insisted that the Dormaa stool predates the Ashanti Kingdom and that any attempt to rewrite history will be met with resistance.

The ongoing feud between Otumfuo and Dormaahene has sparked intense debate among historians, traditional leaders, and political analysts. Some argue that Otumfuo’s claims are rooted in historical records, while others believe Dormaahene’s push for autonomy reflects a broader movement among Bono chiefs to assert their independence.

As tensions rise, the National House of Chiefs may soon have to intervene to mediate the growing dispute. The legal and traditional implications of this battle could shape the future of chieftaincy relations in Ghana, particularly as both leaders continue to assert their positions.

With Dormaahene now facing mounting legal challenges, many are watching to see if he will seek reconciliation or continue his confrontational approach. The coming days promise major developments in this battle between tradition, authority, and historical narratives, ensuring that this dispute will continue to dominate discussions in Ghana’s chieftaincy circles.